|

| Valjean at Knox. Photo by Leonard Borden |

We'd known each other slightly before that year--we were both in the Whitman/Stevens class the previous spring--but usually in a group. Then we were both in Macbeth that fall of 1966, of my junior and her senior year, though we had only one scene together, in which I did nothing but gape at Macbeth and his Lady (played by Valjean), along with the other thanes. But we did acquire that bond and familiarity that actors share when they're in the same production.

She was also an active resident of Anderson House, which became the "experimental" dorm for fourth year women, the experiment being the absence of curfews or a housemother, and relaxed rules on visitations. I got involved in their campaign to resist some sort of re-imposition of restrictions, as the college decided to take the term "experimental" literally, and deputized a stiff-necked member of the psychology department to study their "variables" as if they were mice in a maze.

In any case, while I was back in Pennsylvania with mono for the first part of the winter term, Valjean was just about the only Knox student to contact me and check on how I was doing. When I got back to campus, she was the first person to greet me.

Thanks to the mono I still didn't have the energy for much socializing, but we went to some campus events together and had more one-on-one conversations, lingering at a Gizmo table for hours, interspersing serious ideas and distressing news of the day with peals of mischievous laughter.

One afternoon we had outlasted everyone else at our Gizmo table and sat there alone as it got dark. Eventually Valjean sat up straight and asked, "Shall we to dinner?" "Let's!" I said, as we both got up smiling. Val kept beaming--"That was the perfect response," she said quietly. In that instant we'd both inhabited the same sort of old movie, of bright young things in their tennis whites, with not a care in the world.

The next year Valjean went off to the University of Iowa graduate drama program, and I saw her there several times the autumn after that, when I briefly attended the Writers Workshop. I was mostly being drafted and sadly was not good company, but she hung in there with me.

I saw her briefly a few years later, when we both happened to be on the Knox campus; she was playing the part of a career woman in real life, all made up and dressed for success, but I could tell her heart wasn't in it. That, as it turned out, was the last time I actually saw her.

Years went by after that 1970 moment, and in the early 1990s she called me up. She'd just been to a Knox reunion and wanted to organize friends to go to the next one. Her enthusiasm was contagious but in the end I didn't go. Still, we were in touch by phone and letter and email right up to the time that she was diagnosed with cancer.

|

| Valjean on her last trip to Mexico |

We came close to meeting again a couple of times, including sometime around 2005 when she came to California, but we couldn't work out the logistics. It's a big state.

I realize now that she didn't talk a lot about her past, so I learned much more about her accomplishments, her activism and compassion, and her wide circle of devoted friends from the blog she set up as a focal point for news about her illness. I found out about her diagnosis from an email she sent out, which also asked that all communications go through the blog, a request that I foolishly honored. So it was from the blog that I learned of her death in July 2008. She did not live long enough to see the man she had told me about a couple of years before, Barack Obama, become President. But she lived her last months with the euphoria and anxiety of his first campaign around her in Chicago.

Valjean was in the class ahead of me at Knox and she was fiercely intelligent, so it was awhile before I realized she was about six months younger than me. She was a presence, a force of nature. Anyone who heard her voice knew she was full of life.

I remember Valjean from that winter term, but I don't remember a thing about the literary criticism course my transcript says I passed (with an A). Unfortunately I haven't found anything to jog my memory. A partial draft of something that could have been a paper in lit crit survives, but without indication of what course it was for, if any.

However, literary criticism itself was a major aspect and activity of all literature courses, and of being a literature (and composition) major. I do remember books in literary criticism that were suggested, assigned or often referred to in college. And my reading of literary criticism and books in related areas did continue after college, through to the present.

So this will be my post on lit crit, in college and beyond.

First, to locate my era. At least at Knox College, the trends and virtual cults that overtook and in some ways overwhelmed lit crit in a big way in the 1980s and 90s--the various approaches known as structuralism (and post-structuralism), deconstructionism, semiotics, and more generally as postmodern"theory"-- had not yet joined the conversation, let alone shouted everybody else down. As I've mentioned before, the New Criticism of the 1940s was still the most influential guide, but different styles that for example looked at the writer's relationship to the times were also in the mix. Analysis from other points of view (political, historical, cultural, economic, class structure, etc) was edging in, and the latest approach of McLuhan and media studies was hotly debated.

All that said, there were literary critics that won respect for their criticism and its eloquence, transcending any affiliation with one label or another. (Many were leftists politically and some were Marxists or communists in the 30s; I doubt we knew much of this when we read them in the 60s.) In fact they tended to be highly individual, and often employed a mix of perspectives. What especially distinguishes these works from later lit crit is the quality of the writing. These books were meant to have some of the literary qualities of the books they were about; they were written be read with pleasure and understood by non-specialists.

What is in those books defined as literature anyway? How do they work? How do they fit into the literary landscape and literary history? How do the various works by a particular author relate to one another? To their times and beyond? These are some of the questions addressed by the literary criticism that I remember.

|

| My Anchor hardback has no dust cover and just a blank red surface. This Anchor paperback edition has an intriguing cover design. |

His essay "Manners, Morals, and the Novel" contains Trilling's most famous phrase, when he defines manners as "a culture's hum and buzz of implication." I've since added his slim volume, Sincerity and Authenticity, and his final Selected Essays titled The Moral Obligation To Be Intelligent. I also have a huge anthology of western literature that Trilling edited.

In his essay "The Meaning of a Literary Idea," Trilling takes on the strict New Criticism of Rene Wellek and Austin Warren's Theory of Literature, an earlier lit crit classic, often referred to simply as "Wellek and Warren." I'm not sure I ever had a copy of it until I found a vintage paperback a few years ago. I. A. Richards is another lit crit elder whose name I heard. His books on literature go back to the 1920s and 30s.

A book often mentioned that I did have (and still have) is The Well Wrought Urn by Cleanth Brooks, which is chiefly about poetry. I marked up the opening essay, "The Language of Paradox" and in the next I probably found some answers in the treatment of the play I'd acted in, Macbeth.

The aforementioned names and titles--and probably others--were given to us as the gods of lit crit. Northrop Frye's influential 1957 Anatomy of Criticism may well have been in that company. His name at any rate was familiar enough to me that when I spotted an interesting title on a sale table at Squirrel Hill Books in Pittsburgh in the early 1990s--The Educated Imagination--Northrop Frye as the author made the sale.

I found that slim book very stimulating and generative, so the next time I came across a Frye title, I snapped it up. After re-reading The Educated Imagination a few years ago I became more deliberate--I hunted down Frye titles online, until I had--and read--(two things that do not always go together, of course) a total of 10 of his books.

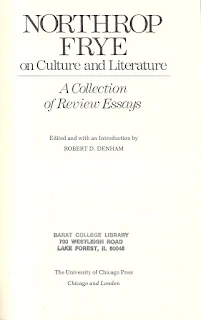

Probably the most interesting acquisition was a collection of short pieces entitled Northrop Frye on Culture and Literature which I bought just a few years ago. Like many books of this kind, the editions available are often library discards. The one I bought was a 1978 first edition hardback, and when it arrived I was amazed at its pristine condition. It was from the Barat College library. Barat was a small Catholic college in a leafy and wealthy Chicago suburb, until it went bankrupt and eventually dissolved in 2005.

This book had been acquired from the University of Chicago Press presumably in the year of publication. Barat had emphasized the arts, but apparently not the work of one of the 20th century's most esteemed literary critics--for on the Date Due sticker on the back there was not a single name. This particular book had led a very quiet life on a college library shelf for a quarter century, possibly untouched, yet outlasted the library itself as well as its college.

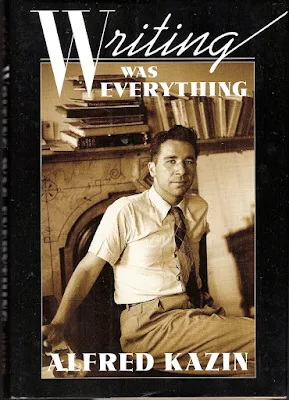

There were other perhaps less exalted names I learned then, probably from essays on specific writers, such as Scott Fitzgerald or Wallace Stevens. Alfred Kazin made his mark with On Native Ground, a study of American prose from 1890 through the 1930s, with an emphasis on realism. He continued writing up to his death in 1998, including memoir and history. One of my favorites is the late Writing Was Everything (1995), an autobiographical celebration of an era and community committed to literature. I have 7 of his books, plus a biography.

Malcolm Cowley, a poet, critic and literary historian, wrote mostly about writers and writing of the modern era. An extra element of fascination for me was that Cowley was originally a western Pennsylvania boy (like me), who grew up to know writers (Hemingway, Faulkner, Kerouac) and critics (Edmund Wilson, F.O. Matthiessen and his Pittsburgh high school classmate Kenneth Burke.) He started out earning his living writing rather than teaching: one of his personal histories is titled --And I Worked At the Writer's Trade. I have six of his books.

Cowley not only knew writers personally (including Hart Crane) but he engaged them in dialogue about their work--particularly Faulkner. He was also one of the American pioneers of what we know now as the interview--the public dialogue with writers--especially in the Paris Review Writers At Work Series. He edited and wrote the introduction to the first collection. (With some effort, I collected all ten of the published volumes. Subsequent interviews live only in the physical magazines and online, as far as I know.)

Edmund Wilson's Axel's Castle introduced many modernist writers to American readers in the 1930s. I don't recall him being among the favored critics in college, and I didn't read him then (except in relation to Fitzgerald.) I've acquired several collections of his bracing and highly opinionated pieces by decade, as well as a more general collection. (My copy of The Triple Thinkers: Twelve Essays on Literary Subjects came to me from the Arts, Literature and Sports Department of the Birmingham, Alabama Public Library via Better World Books.)

Many of these critics concentrated on the modern period of their own lifetimes, and since this was the most recent period we really studied in college, I've remained interested in exploring these writers in depth. So I also have several books by Hugh Kenner (The Pound Era, The Elsewhere Community, A Homemade World, etc.) and Richard Ellman ( Golden Codgers is a more recent acquisition, but in 1967 I had and would revere his biography of James Joyce. I had also added novelist Anthony Burgess' study of Joyce, titled ReJoyce, to my Joycean collection. There would be several more Ellman books added to that group over the years.)

Some novelists and poets wrote interesting lit crit, both the famous (Pound, Eliot, Lawrence, Stevens, Updike etc.) and the lesser known. In fact, poet Randall Jarrell is perhaps better known for his criticism--though he seems unjustifiably overlooked in both categories these days.

I haven't totally limited my subsequent lit crit reading to this early 20th century era by any means. I have studies and biographies of writers who wrote before and after the moderns, including some written in recent decades, such as works by Louis Menard, Margaret Atwood, James Wood, Denis Donoghue, Octavio Paz, Italo Calvino and Ursula K. LeGuin. That's apart from works on literature from elsewhere (or very much here: Native American writers) and what gets called genre literature. Needless to say, there's no death of the author idiocy among them.

I also haven't mentioned here the works on specific writers or periods that were assigned or suggested for specific courses at Knox such as 16th century English literature, or such studies that I've included in earlier posts.

I've also read enough to realize my comparative ignorance of even the usual western tradition, so I have a few more extensive literary histories. My favorite of these is Literature and Western Man by British dramatist, novelist and critic J.B. Priestley. It is a briskly written series of essays from a somewhat covertly Jungian point of view.

In fact, I have more lit crit books than I could ever possibly read, partly for one reason. For years the Humboldt State University Library held an annual book sale, with most of the books being their discards. (Perhaps they still hold it, but I am afraid to know.) For the last hour of the sale, buyers could fill shopping bags with books and get them all for one price. I kept my avarice within decent limits until the years the library started shedding books by the hundreds and thousands. They had to make room for computers and cafe areas, and were depending more and more on online resources. Books just got in the way.

The last sale I attended was truly scary. I saw what looked like the entire works of authors (William Dean Howells was one I remember) stripped from the shelves and sold off. By the end of the sale the dregs included hundreds of books of literary criticism, literary history and biography, mostly published before 1970. I filled up several bags full of them, and they now line my shelves, or are in piles atop them or on the floor, all with their white Dewey Decimal ID stickers with the big black x through them. Among them are several gems, a few are pedantic twittering but many are serious works, analyzing and celebrating writers worth reading--and remembering.

Needless to say, this kind of literary criticism--and literary culture--are relics of a bygone age. And so, I suppose, am I. But you knew that already.

Now that I am no longer a student, or much of anything really, I read literary criticism, history, memoir etc. for the pleasure, challenge and inspiration of reading it, without the necessity of retaining any of it afterwards. Remembered consciously or not, it may still nourish the soul.

Lit crit has it dangers. While it can illuminate, it often distorts and simply denigrates. It sets up orthodoxies (which change, but not often within four years of college) and hierarchies. It can use ideology not as a perspective or starting point but as a litmus test. And as an academic industry, it too often misses the point.

There is in lit crit, as almost everything else, a pack mentality, so that books and writers become defined by a generation of critics. This discourages students and others from reading frowned-upon books and authors.

I began discovering literature in my Catholic school days, so I was immediately familiar with banned books and suspect authors (really most of them except for Cardinal Newman.) Even though I was on guard against this on any grounds in college, I nevertheless was heavily influenced in my reading choices by these judgments, especially when they were, in a sense, the correct answers on graded tests.

So in addition to the lit that academia had not caught up to (from the 1950s on), there were writers from the past I learned to scorn and ignore, including Dickens, Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Frost and many others.

Books could be tainted by criticism of the author's character or prejudices, which is a more complicated issue. Racism and other "isms" are often evident in texts and pointing out instances of them is worthwhile, though evaluating them is trickier.

How much an author's personal behavior and beliefs should influence reading is a vexing question, and distortion or disproportion is part of it. As Alfred Kazin (among others) suggests, writers were often prejudiced as well as cruel, malicious, mendacious, snobbish and arrogant--and so were their critics.