It was a pretty good 72nd year. No one close to me died, or came down with a serious illness or injury, though I certainly know people my age with significant health challenges. The exception is our beloved cat Pema--we're currently nursing her through a terminal illness, making this a sad and anxious time. But as for my health, I'm looking forward to my annual trek up Trinidad Head later today. Yesterday I set my home court record with 7 straight midrange baskets (I can't in good conscience call them "jumpers") and 9 out of 10, before I missed two in a row.

I'm pleased with writing I did this past year, including what amounts to drafts of two short books which I have cleverly hidden within my blogs on the Internet. My recollections--first of books, but especially of my senior year of college fifty years ago-- went very well, by my own lights anyway. The process was fascinating. Reclaiming context through factual research seemed to evoke and free memories, some of which came to me in the act of writing.

Lately I've had episodes of visual memories, which have been rare before now. I'm not good at visualization. "Imagine yourself on a beautiful beach" etc. has never worked for me as a meditation or relaxation technique, for example, if it depends on seeing it. But lately, visual memories have come almost unbidden, and once I've had them (usually on the edge of sleep but not always), they more or less remain accessible.

The past, both culturally and personally, remains my focus, my fireplace (which is what "focus" means.) I'm interested in depth, reiteration, a more thorough exploration, rather than new places and experiences. Fortunately I don't have to defend that choice.

"Don't Want To, Don't Need To, Can't Make Me, I'm Retired."

At the same time, I am exploring new ideas, though they tend to be more like going farther along a path I darted down for awhile before. Some of these bear upon that other area of concern, the future.

The future has looked dark many times in my life, probably most times. But there was always an idea or two that suggested the possibility of light coming into being. That is less so now.

The newest ideas I'm still learning about are actually 20 or 30 years old. It was in the late 1980s and early 1990s, for example, that the scientific ideas informing the Gaia hypothesis were percolating. Its basis was formulated even earlier, in the late 1960s when I was in college (but it was so unorthodox that it never would have been mentioned in a science class.) In studying the atmosphere of the planet Mars, James Lovelock discovered that the physics and chemistry of that planet predicted what it was like. But the physics and chemistry of Earth does not describe its actual atmosphere. There is another element determining and regulating Earth's atmosphere, and keep its temperature fairly constant despite changes in the heat coming from the sun. That element is life.

The Earth is self-organizing and self-regulating through its specific lifeforms. Living systems, from the smallest bacteria to the entire surface and atmosphere, self-maintain. That makes the Earth a single system, and by some definitions, a kind of organism.

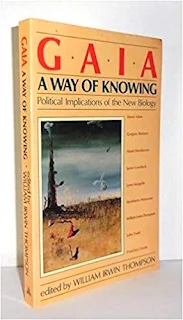

The implications were vast, and go beyond ecology--the study of the Earth as our home--to the study of the Earth as our body. The idea of Gaia was an immediate magnet for various New Age enthusiasts but in the late 1980s, William Irwin Thompson and the Lindisfarne Association published a couple of collections of essays derived from conferences the Association had held since the early eighties. (

Gaia: A Way of Knowing, and

Gaia 2: Emergence).

The authors were serious people, including James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, the scientist who helped him develop the hypothesis, as well visionary cybernetic pioneer Gregory Bateson, visionary neurobiologist Franciso Varela, physicist Arthur Zajonc, botanist and popular writer Wes Jackson, economist and futurist Hazel Henderson and W.I Thompson himself, who promoted the idea that Gaia could be the guiding idea of cultural transformation in the 1990s.

As far as I can tell, there didn't turn out to be a guiding idea of cultural transformation in the 1990s, nor do I know of any guiding idea since. At best, some segments of society sort of caught up to ecological ideas of the 1960s and 70s. Others got sidetracked by computer technology to contemplate bogus ideas like "the singularity" or just got sucked into the social media vacuum.

But lately I have been reading

Slanted Truths, a book of the mid-90s, a somewhat shaped collection of essays by Lynn Margulis and her son Dorion Sagan. (He is also the son of Carl Sagan, and has taken on his father's job of popularizing science, though he's much more his mother's son in the science he attempts to popularize.)

Their essays were mostly published separately in periodicals and are often repetitive (which is actually good, since the ideas are still new and the science unfamiliar) so it is an immersive experience. (These writings are however more coherent than either of the authors speaking: Dorion does not have his father's skills and both are pretty unorganized in the events YouTube has preserved, though Margulis is nevertheless magnetic and occasionally mesmerizing.)

Margulis herself transformed life sciences by concentrating on microorganisms, and showing the crucial role they played in evolution. She also showed that these are the organisms upon which Gaia's ability to self-regulate depend, more than any other. Bacteria is the essential lifeform to maintain the life of planet Earth, including its atmosphere.

I am reading this in the context of a year in which it seems that the collapse of civilization within the next century, and perhaps the fall of the American Republic much sooner, seems more and more likely. On a somewhat longer timeline, the fate of the human species is in question. If the climate crisis and mass extinction are as bad as they seem they will be, homo sapiens may be facing enough reduction that extinction is possible. In a previous climate crisis, homo sapiens were down to perhaps 2500 beings in one small location. Coming back depends on how extensive the changes are, and for how long. Nuclear weapons complicate this further.

Mass extinctions may wipe out all large mammals and perhaps too many keystone species we don't even know about. But the ultimate threat to life seems to depend on what happens to the oceans, and whether we end up killing them.

Margulis and Sagan leave me with at least this hope for the future of life: that bacteria are likely to endure and adapt, and since from them in time came all of the species we know, they can just start again. Raccoons or rats or even ants may be faster to develop but then, does the planet want to go through all this again? I sometimes wonder whether a species that invented helicopter gunships even deserves to survive. Maybe evolution will settle next time on a scenario like that in Kurt Vonnegut's novel

Galapagos, in which descendants of humans are more like porpoises, who frolic in pools with fins, incapable of building anything.

For the near future, Gaia offers some possibility of offsetting the worst effects of global heating, in that we don't understand exactly how life regulates the atmosphere. Perhaps that self-regulation can overcome excessive global heating, although it seems there is unlikely to be enough time to adapt. But maybe.

Which suggest another source of hope: our ignorance. We think we know a lot, but all we've learned are a few limited mechanisms and how to do some stuff, mostly through trial and error. We've just done too much of it, on too large a scale. Because in part there are too many of us.

In fact we know almost nothing about our world and our universe. Steven Wright used to joke: "I bought a packet of powdered water but I don't know what to add to it." We don't really even know what water is. We certainly can't make the stuff.

We've made up all these categories and theories that soon reach their limits, though we insist they are universal, they are "laws." Science has at least acknowledged that Newtonian physics doesn't apply in all realms. (And that's because we know how to do some stuff using the math of quantum mechanics, but we have no idea why they work.) It took recent scientists like Lynn Margulis to begin showing that Darwinian evolution in its traditional definition doesn't apply to everything alive, or even to the origin of species.

Margulis and other microbiologists also showed that many of the assumptions made about how life works in general was based only on larger lifeforms: animals and plants. But many of those "rules" don't apply to microorganisms such as bacteria. Either these rules operated in a limited field or they are generally mistaken.

We use definitions as tools and then get captured by our definitions. The most interesting philosophical essay I read this year,

by Galen Strawson, suggests that the conundrum of consciousness as a non-physical phenomenon may lie in a restricted definition of "physical." The universes of the very small and the very large have shot down a lot of our middle-range assumptions and definitions. With dark matter, dark energy and all the other more or less theoretical aspects of the universe, exactly what "physical" means is (or should be) in doubt.

So maybe there's something we'll learn that we can't now foresee, something that will make enough of a difference to avoid catastrophe.

For those younger than me who will live in the future, hope is a daily commitment to make things better. Hope isn't what you feel, it's what you do. For me, looking at a future that extends beyond imagination, I am buoyed by possibilities we can begin to imagine but can't quite imagine, way beyond anything fantasized in Silicon Valley.

So I greet the beginning of my 73rd year with a poem by Emily Dickinson. She was a favorite of Lynn Margulis (though admittedly not of mine)--I saw a line of this one that was sort of quoted by Dorion Sagan. The whole poem however is what I want to say:

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

P.S. I've added a "birthdays" label to such posts in prior years. But two of the more extensive are on another blog:

Turning 60 and

Turning 65.