TV and I grew up together. This is our story. Latest in a series.

TV and I had grown up together, and then grown apart. But television as I knew it continued to contribute to my life, though in more sporadic and selective ways.

When the alternative weekly I edited—Newsworks in Washington D.C.—folded in 1976, I returned to Greensburg to chill out and plot my next move. I was soon offered a job as an editor at the Village Voice in New York, but just before that deal was completed, the Voice was sold and all hiring cancelled. So I turned to reviving my magazine writing, as well as other writing.

Which in the present context is all to say that I had a lot more time for television. This would not be the first or last period of my life when I needed some rescue provided by books, movies and TV, but it was acute in those years of “inexpensive isolation” (as I later described them), when after a period of uncompensated writing and searching for an agent, an article led to the protracted effort to get a book contract based on it, followed by the research, writing and then re-writing, and all the elation and trauma surrounding the fraught odyssey of its publication and its aftermath—a period that extended through most of the 1980s. I had family and friends and something of a social life, but otherwise the rhythms of my life and identity were disrupted to the point of shapelessness, and I often felt lost and bereft.What kind of rescue did TV provide? It certainly offered the mind-numbing kind in abundance but I valued other, more positive, active and specific contributions, and in this last sections of this series, I want to acknowledge some of them.

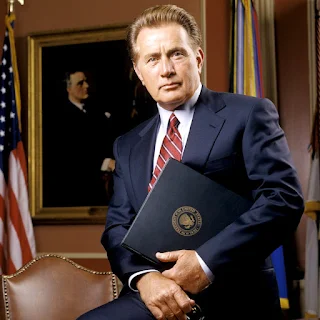

Some forms are pretty familiar to others: the TV shows or series that create an alternative world to painful aspects of the real one. So I share with many the need and gratitude for M*A*S*H during the Vietnam war, and The West Wing during the Bush/Cheney years. In a less specific sense, Star Trek served this function for many over the years, and it did so for me. Star Trek modeled the soul of a better future, especially in its most globally popular series, Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94.) It was personal nourishment and a beacon to future possibilities: not in terms of technology but attitude, generous ethics and community.Also in the late 80s and early 90s, I found the series Thirtysomething more than just entertaining and generally informative on what my generation was going through. For much of that time I was employed as a senior writing at an editorial firm with business and government clients, which was my first (and last) experience in that kind of organization. It turned out I learned more about what I was experiencing from the advertising firm portrayed in Thirtysomething than any other source.

But other forms of TV rescue were more personal, more linked to my circumstances in a time and a place. This was most acutely true in those late 70s and 80s in Greensburg. I suspect others have shared these experiences, at different times and places, and with different television.Most of my television viewing continued to be late at night. I still watched talk shows. The Dick Cavett Show was a valued, even essential oasis while it lasted, but it was ended in 1975. Tom Snyder’s quixotic Tomorrow Show was still on NBC in the early 80s before it too disappeared. Watching other talk shows was like attending old rituals, comforting in a way but often empty. However, anything approaching intelligent or even amusing conversation was welcome.

|

| Paul McCartney brings Johnny a birthday cake |

For a long while his success puzzled me. I first watched him on his afternoon show, Who Do You Trust?, and though he was a compelling presence, it was hard to say why: basically he was a skinny guy who seemed to be restraining himself from telling dirty jokes. On the Tonight Show he shamelessly adapted bits and characters that Steve Allen, Ernie Kovacs and Jonathan Winters had originated, but he made them his own. As he relaxed into his silver-haired years, he assumed a mastery over that show and its environment. Within its ritualized context, he added the human element, especially when he knew his guests. And he could be funny.

Carson was said to be painfully shy and so socially awkward that he avoided social events. But he found elements that worked for him, particularly his adaptation of the reaction take that he freely admitted he learned from Jack Benny. There was however an earnestness about him that appealed to me—the impression that he was a serious person, if not as intellectual as Cavett or Steve Allen. He also seemed to be without prejudices, and seldom belittled his guests. He seemed a generous, decent man who knew he was limited, and pushed against his limits, but not too hard. The audience at home was part of all the ritual, and they saw themselves in Johnny Carson. |

| Magic Johnson on Arsenio Hall Show |

I continued to watch movies, of course: on TCM and AMC, and HBO and whatever other premium channels were part of the package, like TMC. What was new were the late night reruns, not locally syndicated but through networks. So I watched old episodes of Magnum P.I., Kojak and Baretta, shows I hadn’t watched (and didn’t watch) in prime time. I knew I was scraping the bottom for solace here, and I wasn’t grabbing role models (although the catchphrases “Who loves ya, baby?” “And that’s the name of that tune,” were catchy) but they gave me the quicker rhythms, personality and style that real life wasn’t providing.

Early in my exile I was devoted to the Lou Grant series starring Ed Asner. I'd watched the Mary Tyler Moore Show of course--and even happened to be in downtown Minneapolis at the precise moment she was filming new inserts for the introductory montage of the show. I watched her walk by in her brown trenchcoat. It was my first time in Minneapolis and it might have been hers as well. Considered a spinoff, Lou Grant retained some of the humor but was basically a serious series about newspaper reporters and the social issues they confronted in their stories. This was my neighborhood in a way, and I loved entering their world. Once again, Monday nights at 10 p.m. were sacred.At a later point, the cable channel A&E was alternating late night episodes of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes series starring Jeremy Brett (from Granada TV in the UK) with another UK series, Lovejoy, a comedy/drama about an antique dealer—a “divvy” who can divine the authenticity of an item-- who solves antique-related crimes, often in self-defense.

A&E was the first to show Lovejoy in the US, while the Sherlock Holmes series premiered on PBS before A&E. I might have seen it on PBS but like the original Star Trek and the aforementioned series, seeing it every night (or several nights a week) gave it a stronger, more consistent presence. When I was watching these, I was most fascinated with Lovejoy: the rogue and outcast who always finds a way to right a wrong, or at least outfox the more unscrupulous. |

| Watson (Hardwick) and Holmes (Brett) |

His Holmes is magnetic (and occasionally frenetic) as well as nuanced and complex. At times Brett plays him with what Hardwick calls “Edwardian acting,” the high style of early 20th century theatre, a brilliant notion even historically for the advanced detective of the late 19th century, for whom deduction was a performance. Even when I know the story, even the lines and the moves, it’s a joy to revisit Brett’s Sherlock. I also love the men’s clothes—the long coats, the tweeds with matching caps. I admired much of the BBC modern times Sherlock series and the CBS modern times Elementary series, but Brett’s original period series wears the best.

While Brett’s style remains a chief attraction, at the time I gravitated more to Ian McShane as Lovejoy on A&E (though on DVD many Lovejoy episodes are enjoyable but they aren’t as consistent as Brett’s Holmes.) Lovejoy also affected my style by favoring t-shirts with suit jackets (years before Miami Vice changed everything with their ultra-slick ensembles.) Again, this attraction was as much aural (the way they spoke—even their diction) as visual. These late night forays added some buoyancy to my days.I remember two other shows from the UK were introduced on late night television in the US, this time by our PBS station, WQED in Pittsburgh. Both I believe were on late at night once a week.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy came into my world unheralded, sneaking in very late on what I remember as Sunday night. PBS apparently re-edited the original six episodes from the BBC into seven half- hour programs. I had no idea of the history of this Douglas Adams project in the UK: a novel, a radio series, a stage show and an LP, before this TV series had first aired in England two years before. The books were yet to come.So I was a complete innocent--I didn’t know what would happen. When the computer Deep Thought was ready to answer the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything, I didn’t know what it would be—I had to wait until the next episode. There were wonders after wonders.

The production was a bit clunky but forgivable in such an imaginative romp, as if Star Trek had married Monty Python. The sets were only slightly above Captain Video level, but that became part of the charm. The animated interpolations were priceless, and overall, the wit was astonishing and most importantly to me, nourishing. One of the things I needed from these shows was that their effect, their style and worldview would linger for as long as possible, until lost in the morass and vocabulary of everyday life.Speaking of Monty Python, their Flying Circus series was introduced on PBS in the 70s, and though I watched episodes when I ran into them, I was for some reason never really a big fan. They were funny, and they weren’t.

I was however a fan of a few PBS shows ostensibly for children, mostly for their sly humor. I caught a few minutes of Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood (and later watched a day’s filming and met Mr. Rogers himself) and Sesame Street here and there, but in the early 70s I tuned in as often as I could to The Electric Company (the original one, with Rita Moreno and a young Morgan Freeman as Easy Reader) and later to Mathnet, partly because in both there was usually a layer of subtle but hilarious humor for adults.Mathnet was essentially a parody of Dragnet, and once made an elaborate inside joke about Citizen Kane. The Electric Company included a daily parody of soap operas, “Love of Chair,” in which (as with most soap operas) almost nothing happened. Each segment ended with the question, “And what about Naomi?” with the quintessential organ sting.

A few years before A Hitchhiker’s Guide appeared, another BBC series began appearing late at night: the (then) latest incarnation of Doctor Who with the eccentric, enigmatic but magnetic Tom Baker as the Doctor. It appeared unheralded on the Pittsburgh PBS station WQED. I was blown away by it---after pretty much memorizing all the episodes of Star Trek made in the 60s, I was hungry for another sci-fi world. But I don’t remember it as being on for very long. |

| Peter Davison was the Fifth Doctor. |

It was later that I got the opportunity to saturate myself in the Whovian universe. Back when WQED was an NET educational channel, it farmed out some instructional programs to its UHF subsidiary WQEX, channel 16. But as mentioned previously, cable TV gave the UHF channels with a weaker signal a level playing field and new life. So in the 1980s, WQEX remade itself as the spunky “Sweet Little Sixteen,” with a visibly youthful on air presence, and a slate of offbeat syndicated programs. Its first and most enduring hit was Doctor Who. QEX promoted it with a Pittsburgh-based Doctor Who convention, and most importantly, ran an episode every day.

WQEX started with the Tom Baker episodes—seven seasons worth in the late 70s to early 80s. As everyone must know by now, the Doctor is a Time Lord who travels in a TARDIS disguised as a 1950s London police box. He usually travels with one or more companions, often young women. Every so often the Doctor “regenerates” and takes on a new appearance and personality so there had actually been three Doctors with different actors before Tom Baker and at that point in the late 1980s, two more after him.Doctor Who was so popular with the QEX audience that, apart from encouraging the running of a raft of other old BBC shows (some of them dubious) the station acquired the rights to show all the existing episodes from past Doctors, and eventually each new episode as seen in the UK until the series went into hibernation in 1989.

I don’t know how many other US stations did this but I doubt there were many. I was probably among the few in the US who had the opportunity to see all surviving episodes of Doctor Who, from its first in November 1963, through the Tom Baker stories and beyond them to the Peter Davison and Colin Baker episodes and eventually the last ones with Sylvester McCoy in 1989. There was no more Doctor Who after that until the series was reimagined and restarted in 2005, though religiously keeping continuity. Eventually these "classic" episodes became available to US viewers through the BBC cable and streaming channels.

At that point my favorite Doctor far and away was Tom Baker (only supplanted—but not entirely—by David Tennant in the new iteration.) His mixture of whimsy and high intelligence, a kind of Time Lord Lewis Carroll, was a new sort of role model. I had already identified with the alien Mr. Spock—this was a different way to accommodate my alienation. (All of these protagonists were outsiders of a kind, and I could not help but identify.) I liked his style, too—a kind of post-60s look, with long coat, floppy hat and very long scarf. I had them all in the closet, including a very long scarf with better colors than his. As I transitioned my life away to new adventures living and writing in Pittsburgh, his long hair with wild curls was an easy addition (for as long as any of that lasted.)The wit of the Tom Baker Doctor Who was deepened when Douglas Adams wrote for the show and became its script editor for a year--Adams of course was the author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide. Adams was a fascinating writer and talker-- especially on ecological subjects there is no one who could be succinct and dramatic as he could. He wrote a couple of funny and charming cosmic detective novels, too. His early death remains a huge loss.

Much later, another British series important to me was Foyle’s War. Its format was unique: each episode marked a point and an issue in World War II Britain, wrapped around a complicated crime mystery on the homefront, usually murder. The UK's ITV produced it, and over here PBS featured it in its Mystery! series.

It had a rocky

television history in the UK and therefore a sporadic presence in the US but I saw enough of it to more recently obtain the DVD box

set and immerse myself in its stories and its world. The conception, execution

and historical depth and accuracy as well as the creative weaving of a good

mystery by its main writer, Anthony Horowitz, are all breathtaking, as is the

addictive performance of Michael Kitchen as police superintendent Christopher

Foyle, himself a model of rectitude.

Partly because of the UK’s Official Secrets Act, quite a lot about the

behind-the-scenes war effort in England was only revealed in the 21st

century, so a lot of intriguing World War II dramas emerged.

My hometown loneliness and alienation were emphasized by the daily ramifications of the fact that almost nobody—and almost nothing on TV—quite shared my sense of humor. This became acute as the horrifying, depressing, Orwellian 1980s began. At that point, Saturday Night Live had hit a long dull spot, and Monty Python (which I wasn’t crazy about anyway) was no longer regularly shown. But suddenly, there was the best of all: SCTV was on the air!

|

| SCTV station manager Edith Prickley (Andrea Martin) |

Then in 1981, the NBC music program The Midnight Special suddenly ended production, and the 90 minute post-midnight Friday night slot opened up. SCTV was an inexpensive alternative, a stopgap that became a cult hit.

After midnight was my prime time (and I believe the show was repeated even later, after 2 am) so I became an avid viewer and grateful fan. On its best nights, all 90 minutes constituted the funniest show on television, and even on uneven nights, there were always hilarious moments.

There were variations in the cast over the years but the episodes I saw mainly featured John Candy, Joe Flaherty, Andrea Martin, Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, Dave Thomas and Rick Moranis. (Harold Ramis, Robin Duke and Martin Short also appeared at different times. Short introduced his defining character, Ed Grimley, on SCTV before he moved to Saturday Night Live.)

All these cast members went on to some degree of Hollywood and US television success--Candy made the biggest splash initially, Moranis starred in the “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids” series, and most recently Eugene Levy and Catherine O’Hara won Emmys for their performances in Levy and Son’s series Schitt’s Creek. In addition to her comic roles, Andrea Martin has been nominated for the Tony Awards’ Best Featured Actor in a Musical a record five times.

|

| Catherine O'Hara as "Lola Heatherton" |

|

| Woody and Bob Hope |

Flaherty further exploited his Pittsburgh roots, for instance by narrating a horror film, Blood Sucking Monkeys From West Mifflin PA, providing western Pennsylvania geographical details and interpolated Pittsburgh accents. For the initiated it’s a reminder than indeed one of the classic horror films of modern times, Night of the Living Dead, was shot in Pittsburgh—with Bill Cardille in the cast playing a news reporter. Later in SCTV’s run, the cast performed a series of horror films starring John Candy, including Dr. Tongue’s 3-D House of Pancakes, which also lampooned their cheap 3-D effects.

What turned out to be their most popular and characteristic bit was a parody of a Canadian public access show, The Great While North, in which two rural brothers in stocking caps, Doug and Bob McKenzie (Thomas and Moranis), drank beer from cans while sniping at each other about “today’s topic.” It was a rage in Canada and enough of a novelty in the US to lead to a feature film, Strange Brew. |

| Polka stars the Schmenge Bros |

Expanding on television’s trivialities can be enervating in bulk, but much of it still works for me, along with the memory of feeling part of a rowdy, imaginative and wildly fun group, even in the distant isolation of a solitary Friday night.

Apart from SCTV, the last several aforementioned shows from the beyond the US first appeared on PBS (though SCTV eventually was shown there, too.) These weren’t the only public television programs that nourished and saved me, even directed me, in those years, from the 70s into the 1990s. Those shows are featured in the last episode of this series, next time.