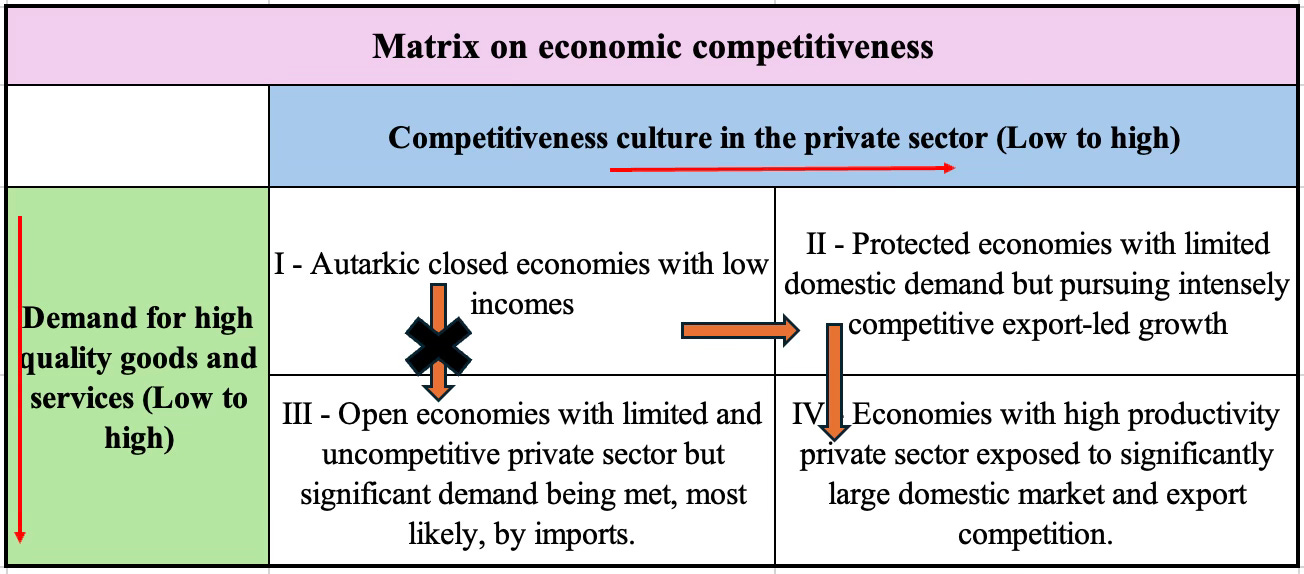

Over the years, I have blogged numerous times, highlighting corporate India’s singular failure to create world-class companies and products. This describes a scorecard of corporate India over the last three decades.

This failure is now being ventilated by government officials and corporate leaders themselves. See this, this, and this.

Nothing manifests this failure more starkly than the IT industry. There’s a compelling argument that, despite all its acclaimed successes, India’s software industry will also be seen in economic history as a canonical example of stagnation and failure to move up the value chain. Thanks to a fortuitous confluence of factors, India gained a head-start in the software industry, an industry at the cutting edge of technology innovation. It even had large multinational companies with the finances and talent to become global leaders in the industry. Further, in the last two decades, the industry has spawned technologies with transformative potential - SaaS, IoT, cloud computing, automation and robotics, data analytics, and now a general-purpose technology, AI.

The industry could have become the springboard and platform for innovation and productivity growth, and for taking the economy to the next frontier. It could have become the anchor for the mass flowering of an ecosystem of technology startups that would be pursuing cutting-edge innovation.

Unfortunately, India’s large software firms have foregone all these opportunities and preferred to stay attached to low-value, manpower-intensive services. They could have capitalised on their industry headstart to move up the value chain and become innovative product companies. They could have provided India with the invaluable anchor around which R&D and innovation could have flourished. Instead of breaking out and leading the way for the rest of corporate India, they have fallen prey to the country’s dominant corporate culture.

Anuj Bhatia has a very good article on where India’s software firms lost their way and failed to capitalise on their head-start and contribute more meaningfully to national economic

Take a look at India’s biggest tech companies. They are all ‘services’ companies, like Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, and Wipro, and have nothing to do with the creation of IP. They essentially acquire clients and do coding for them at a cheaper cost, primarily handling maintenance work. They are not developing software or platforms that they sell to consumers or enterprises. Ask anyone who works for TCS, and they will tell you the difference between working for a services company and a product-facing company like Google. A lie has been sold for years that TCS and Infosys are software companies. However, in reality, US tech companies lead in software, including the likes of Microsoft, Oracle, Salesforce, Adobe, and Google. While India’s services companies may create jobs, they don’t drive innovation, and they certainly don’t position India as a tech powerhouse in the future.

And this is about the importance of IP

It all comes down to intellectual property, and India certainly isn’t an IP-based economy. Intellectual property is the most prized possession a tech company or startup could have… IP can protect you from competitors using your tech, giving you a competitive edge, securing funding, and even safeguarding you from being acquired by a large company. Take Apple’s iPhone, for example. The iPhone’s design, software, product name, concepts, patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets all fall under IP. Some may say the iPhone is a smartphone, but Apple never calls the iPhone a smartphone, and the reason is… well, the iPhone is a platform. That means Apple has exclusive rights to the platform and can expand it, create new products, develop solutions, tweak software algorithms, or make changes to the manufacturing processes whenever it feels. Hence, Apple protects its intellectual property, which is why the company’s top lawyer, Kate Adams, Apple’s General Counsel, earned a compensation of $27.2 million last year.

Similarly, Android is a trademark of Google, and that’s how the company controls the smartphone market being the owner of Android and Play Store. While Apple follows a closed model with iOS, the software powering the iPhone, Google gives Android for free to any company but charges a licensing fee to use the “Google Mobile Services” suite of apps, which includes the Google Play Store. Nintendo, too, is sensitive about its IP, which includes the characters, franchises, game titles, logos, and designs associated with its video games, such as Mario, Zelda, Pokémon, and Animal Crossing, among others… The point is, without intellectual property, patents (for example, Apple filed 5,000 patents for the technologies that contributed to the development of its Vision Pro headset), and a mechanism to protect your IP, it is hard to create a tech company with a foundation based on original ideas and creativity. And these are areas where India lacks in both aspects. This is why we have not seen an AI research lab like OpenAI in Bengaluru or a product like the iPhone emerge from India. All of this is because we never tried to develop the technology or take risks.

The article also makes a point about claims of India attracting tech companies.

We always talk about how big the market is and why tech companies are setting up shop in India. Of course, any major tech company would like to come to India: a) to access the large talent pool, and b) because there is little competition from local tech companies. However, the same tech companies face a lot of competition in China, where they are barred from doing business and have often failed to compete with local companies. But China itself has created its own unique tech ecosystem (take WeChat, TikTok, and how Huawei has finally ditched the Android mobile operating system for its own proprietary, HarmonyOS, for example), and that has helped it gain technological know-how to power its economy and challenge the geopolitical order…

Until we own platforms—be it on the hardware side, software, or cloud—and build the ecosystem, our tech companies and startups won’t be able to transform into tech giants. India Inc. may be keen on collaborating with US tech giants (and that has been the case for years), but that doesn’t change India’s position in the tech world. No tech company (or country, for that matter) would want to share its trade secrets with others—think of formulas, IPs, research and data, and algorithms.

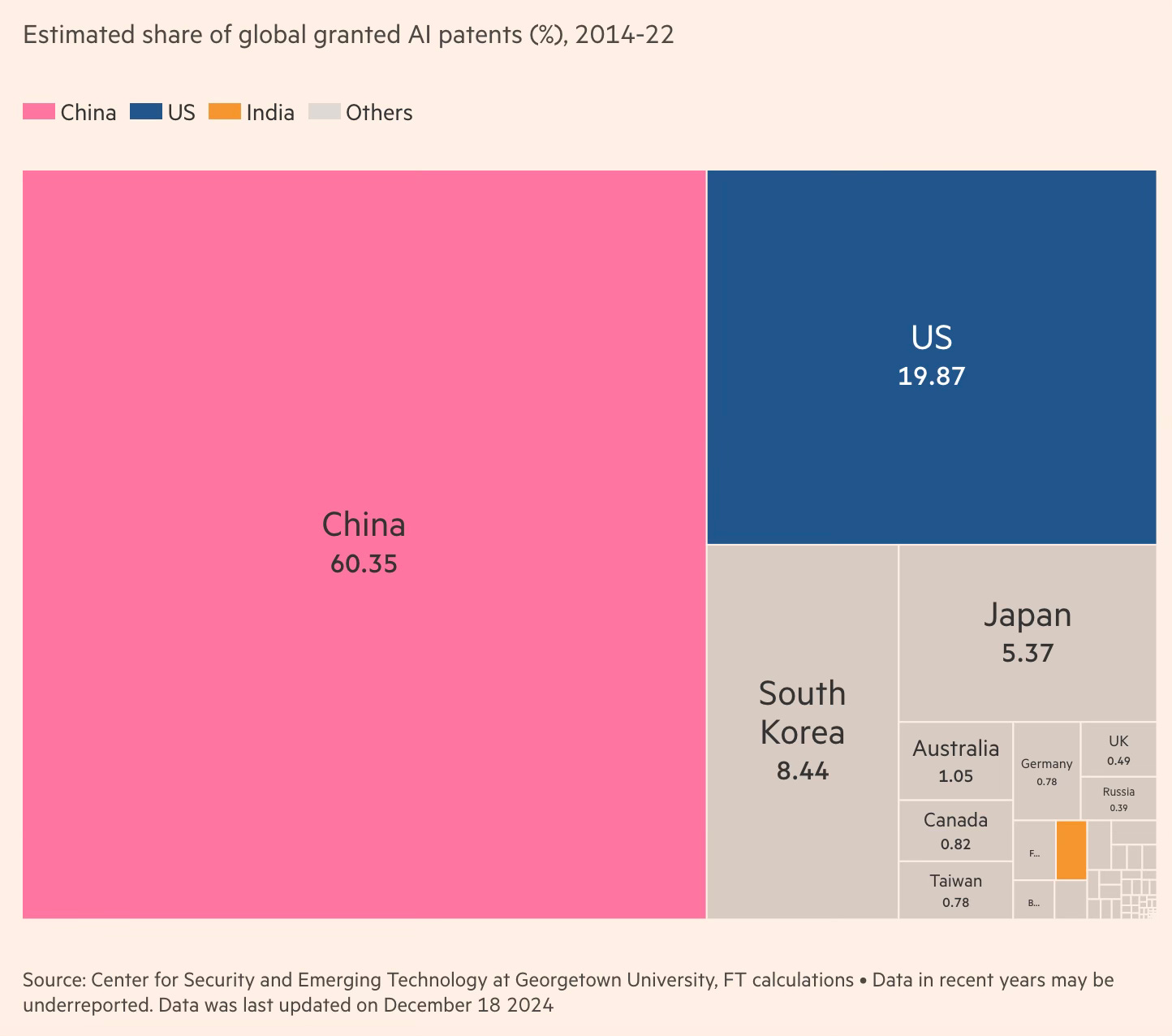

In this context, it’s not surprising that India’s share of global granted AI patents was an abysmally low 0.22%, far below even countries like Australia, South Korea, Cananda, and Taiwan.

Of the $43 bn worth of AI investments globally in 2024, India got just $179.3 million. The Indian technology majors’ investments in AI pale into insignificance before the US Big Tech and Chinese firms.

On similar lines, I have written earlier on our disappointing startup landscape. Forget cutting-edge innovation, they have struggled to meet any of the several development problems that a country like India faces.

It remains to be seen how the much hyped Edtech unicorns will go beyond marginally improving the learning environment of a tiny sliver of students from middle-class families to helping improve the massive problem of poor learning levels that affect more than 90% of Indian students. Or whether Agtech firms will address any of India's several agriculture sector problems. Or the biotech and medtech companies will address the problem of access to affordable and good quality health care for more than 80% of Indians. Or whether the fintech companies will help address the problem of improving financing intermediation by increasing access to mass-market financial products and increasing India's financial savings, besides making formal finance mainstream for the 80% of the labour force working in the informal sector. Or ensuring access to finance simple for businesses in the informal sector. Or whether, like Alibaba's rural Taobao's, India's e-commerce sector has significantly improved market access and incomes in the aggregate to small manufacturers and traders.

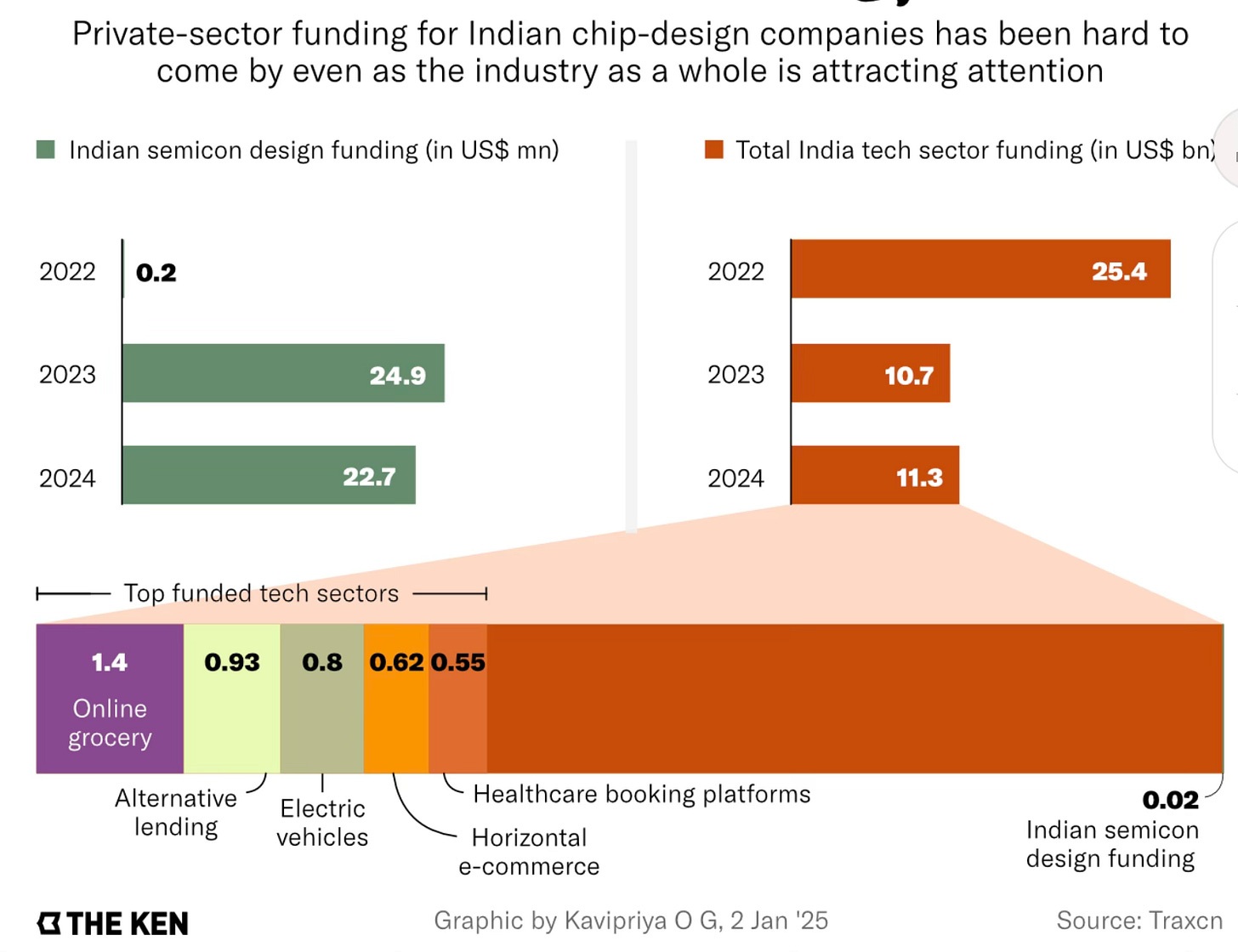

It’s difficult to identify startups that have managed to break into the top echelons or have the promise to do so in areas like cloud computing, IoT, AI, data analytics, robotics, quantum computing, chip design, etc.

Instead, India’s startups appear content to follow the footsteps of the IT firms and focus on the simple, low-hanging fruit of copying consumer-facing services like e-commerce and media.

Just 5% of Indian startup funding went into DeepTech sectors, compared to China’s 35%. Semiconductor chip design, for example, has attracted just about Rs 200 Cr each in the last two years.

Of the $2-3 bn or so of VC capital raised from India-based investors (data is very difficult to get, and most likely is even lower), very little went into these risky and innovative areas. This low level of funding of riskier areas like deep-tech belies the optimism that the first generation founders and investors from the large and growing number of unicorns and decacorns would plough risk capital into these cutting-edge areas as in Silicon Valley. They have instead preferred primarily public markets and secondarily only the derisked and safer areas like consumer technology, healthcare, real estate and infrastructure.

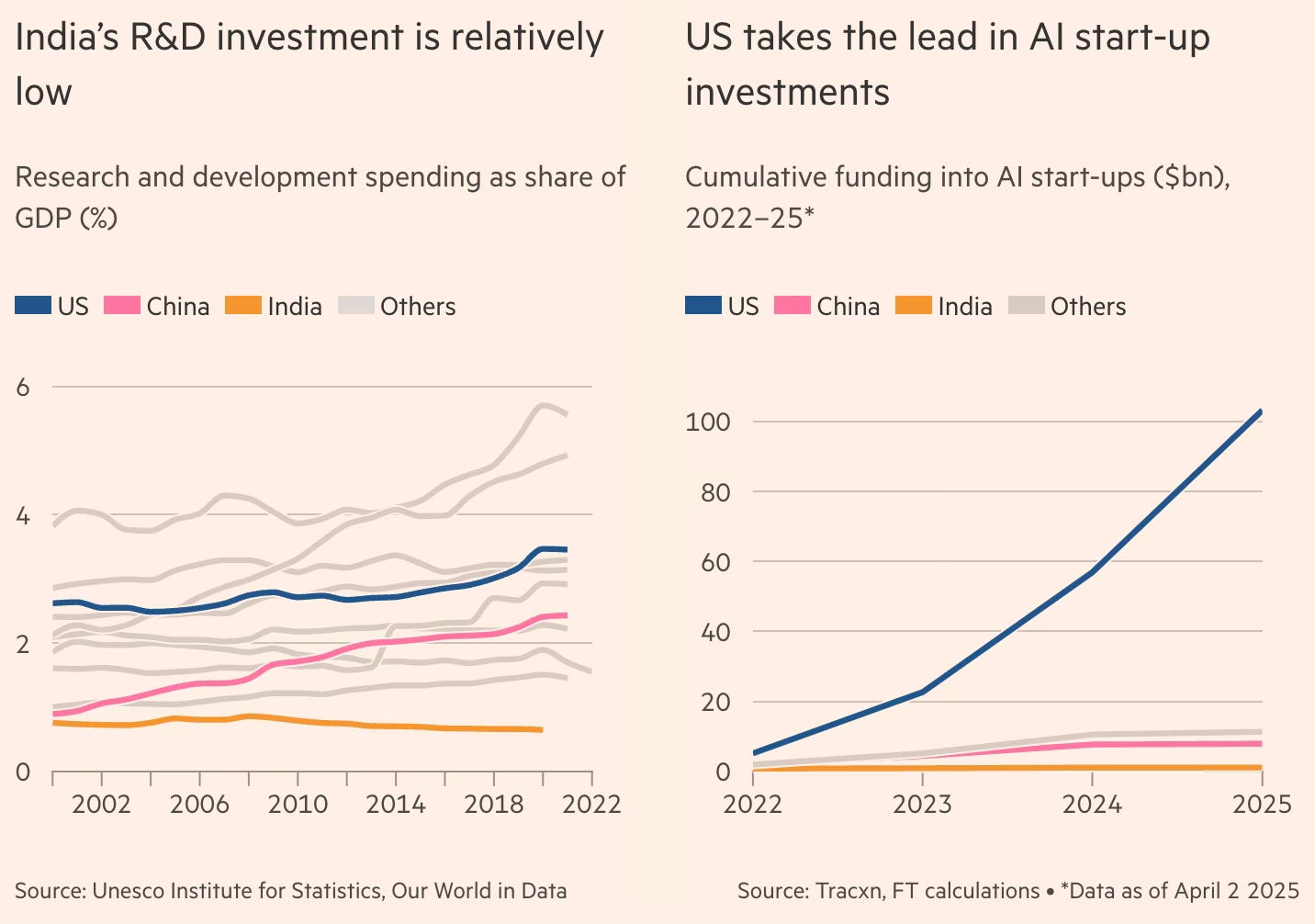

This is also reflected in the aggregate corporate expenditures on R&D, a topic on which I have blogged here recently. India’s gross expenditure on R&D is less than 1% of GDP, far behind the US (3.5%) and China (3.4%). Further, it has been falling continuously since peaking at 0.86% of GDP in 2008 and stood at a long-term low of 0.65% in 2020. The cumulative funding that went in AI startups in India in the 2022-25 period was just $1.09 bn, compared to $7.89 bn for China and $103.21 bn for the US.

This disappointing reality is also reflected across sectors. Take the example of consumer durables manufacturing.

The Ken has an article exploring the air conditioner manufacturing industry in India. With rising temperatures, ACs, once considered a luxury product, are now a necessity. Reflecting this, AC sales have been growing at around 20%, double that of other home appliances, and are estimated to be 12 to 12.5 million units. The Rs 27,500 Cr ($3.3 bn) industry is expected to double.

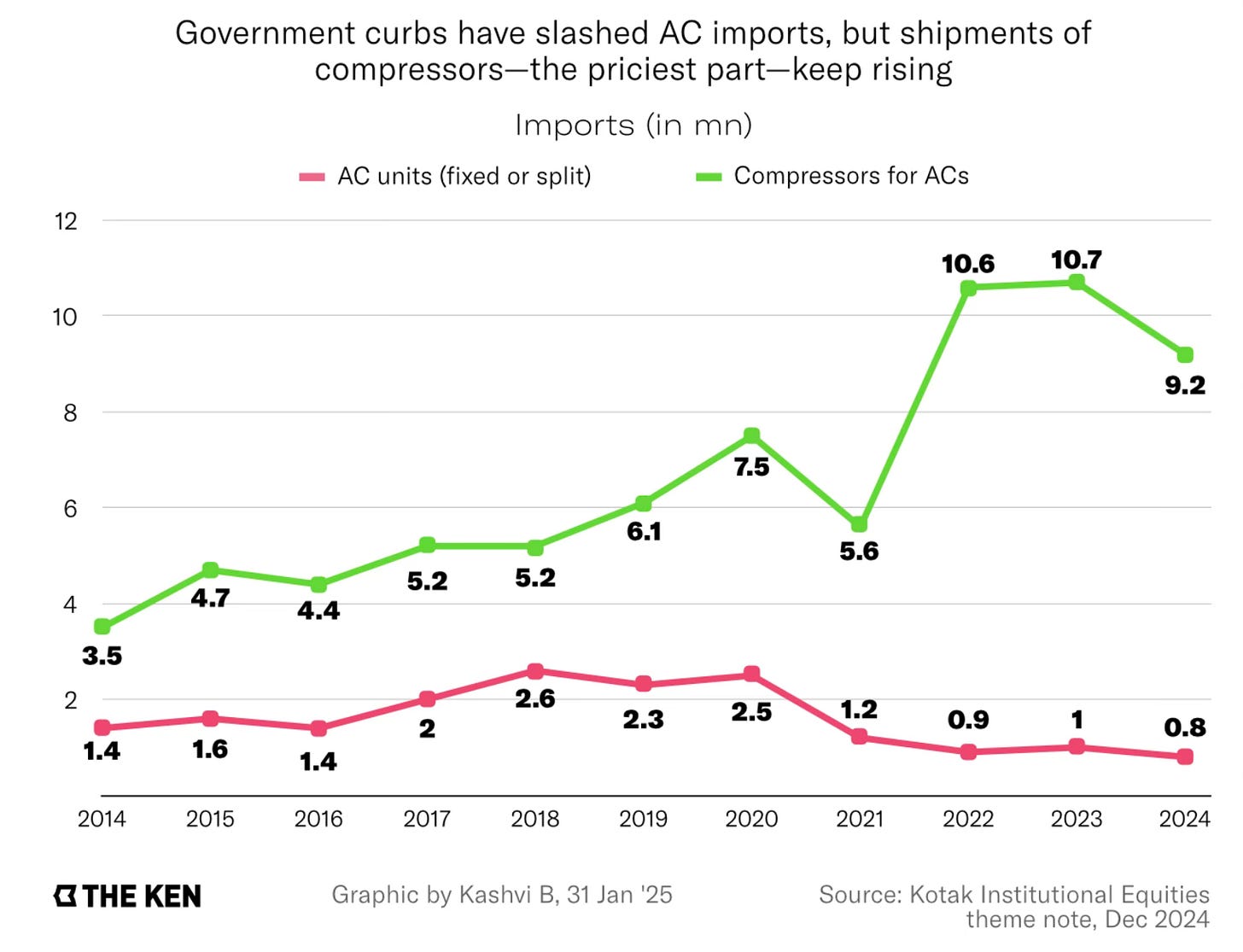

The market leader is Tata-owned Voltas, followed by others like Blue Star, Daikin, Lloyd, LG, Godrej etc. Despite the PLI scheme for white goods launched in 2021, more than 60% of the AC components are imported. In fact, 65% of the compressors, which makes up 30% of the product cost, are imported from China.

The three main domestic contract manufacturers are Blue Star, Amber Enterprises, and PGEL. Compressors are manufactured by just four companies - Guangdong Meizhi Compressor Co. (GMCC, a Midea Group company), Highly India, Daikin, and LG Electronics. The first two are Chinese and the others are Japanese and South Korean.

The uptake in PLI for compressor manufacturing was confined to just two companies - Daikin and LG. Voltas joined only in the third round with a Rs 256 Cr investment. Godrej and Havells, the other big domestic brands, skipped PLI completely. Others focused on the cheaper, lower-value components like heat exchangers and plastic moulding.

Like with most others, the unsatisfactory response to domestic manufacturing of compressors and components has to do with the Chinese competition. Even with higher import duties (it has gone up by 19% over the decade), importing them from China is still cheaper than making them in India. In particular, high-value components are not incentivised by small sales incentives. The article mentions that “localising production would be at least 25% more expensive than relying on Chinese imports.”

In this context, an oped in The Indian Express by Anand P Krishnan compares the private sectors of India and China and points to how they have taken the lead in the latter in national economic growth.

According to China’s State Administration of Market Regulation, as of 2024, there are over 55 million private companies in the country. The private sector accounts for over 50 per cent of tax revenue, over 60 per cent of GDP, over 70 per cent of technological innovation, over 80 per cent of urban employment, and over 90 per cent of the total number of enterprises (in comparison, India’s private sector has a share of 36 per cent in tax revenue, 91 per cent of GDP, 36 per cent in technological innovation, 11 per cent in employment, and over 95 per cent of the total number of registered enterprises).

He writes about how the Chinese firms have leveraged their strategic advantages to strngthen their roles.

Chinese private companies, with their sleek and sophisticated products, have been able to connect with global consumers and are pivotal entities in building an ‘industrial diplomacy’ – to borrow the phrase from sociologist Kyle Chan – to reshape global production networks and make them centred around Beijing. This is visible in a range of modern sectors and industries, that are qualitatively superior and critical in a technologically interconnected world, such as Electric Vehicles, consumer electronics and digital gadgets, lithium batteries, and solar panels. Chinese private companies form vital nodes in global supply chains in these industries, and their inextricability is used by Beijing for competitive advantage. Through these companies, China has remained attentive to building backward and forward industrial linkages – making components and specialised machinery, along with developing skilled personnel with the technical know-how – and holistically dominates the wider ecosystem while also guarding against the sharing of technology. The ability of Chinese smartphone companies to endure and build a loyal consumer base in a country like India (given the hostile geopolitical equation) is a testament to their adaptive capabilities.

All this necessitates deep introspection within corporate India about its role in economic growth.