In the context of China’s stifling dominance across manufacturing supply chains, and as industrial policy interventions proliferate globally and the WTO is rendered comatose due to the dysfunction of its Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), it may be time for India to re-assess its industrial policy instruments, especially concerning export promotion.

The WTO’s Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) Agreement categorises two kinds of “prohibited” subsidies - those “contingent on export performance” (Article 3(1)(a)), and those “contingent on the use of domestic over imported goods” (Article 3(1)(b)). It allows for subsidies that are specific to enterprises, industries, and regions.

When the SCM and other WTO Agreements were being negotiated in the nineties, it was thought that only the subsidies contingent on export performance would be trade-distorting in any significant manner. It was thought that the subsidies specific to enterprises, industries, and regions (or the economy as a whole) could not be sustained at the scale required to distort trade in particular products much less global trade in general.

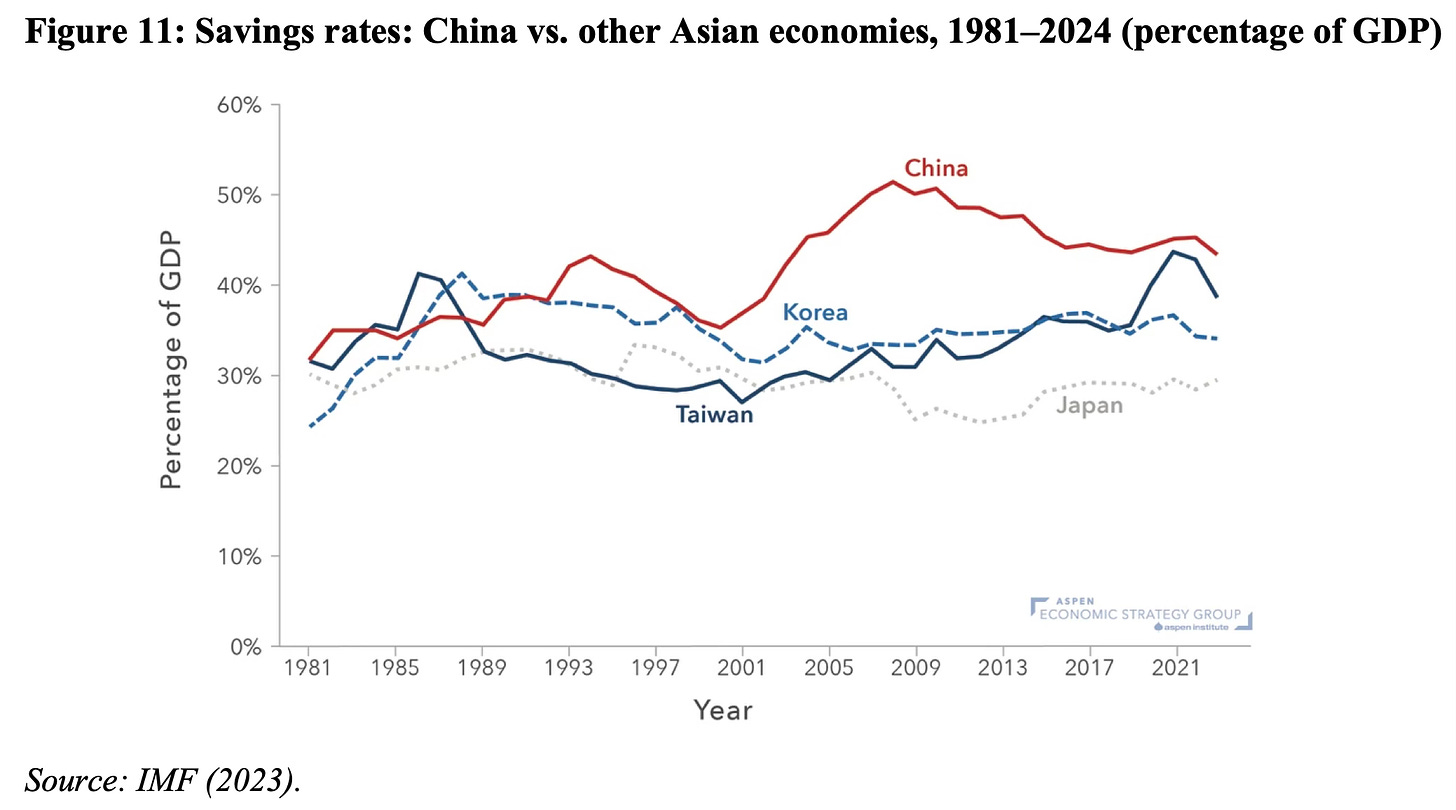

Nobody anticipated China’s extraordinary scale of economy-wide industrial policy subsidies. It’s estimated that China spends 5% of GDP annually on its industrial policy, compared to 0.4-0.6% of GDP for US, Japan, and France and 0.9% of GDP for South Korea. India’s annual expenditure on its flagship production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme is a modest 0.15% of GDP. In the 2000-18 period, Chinese Government Guidance Funds have given over $1 trillion in capital and guarantees to more than 28,000 companies. As part of the Made in China 2025 initiative, the government committed nearly $300 bn in 2018 with an additional $1.4 trillion after Covid 19 to achieve technological self-sufficiency and global leadership in critical sectors. All told, in sectors like semiconductors, steel, and aluminium, China makes up 80-90% of all global subsidies.

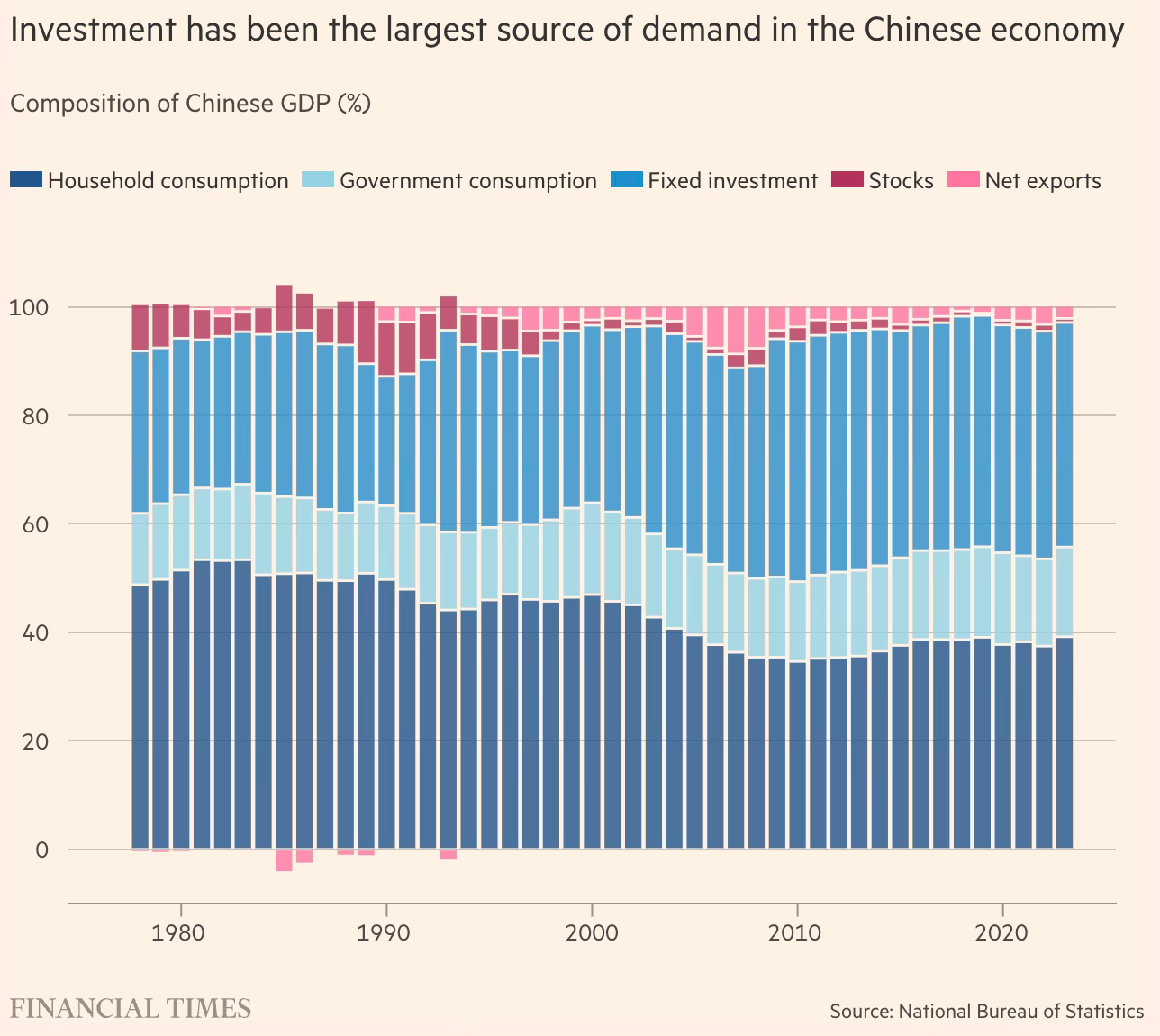

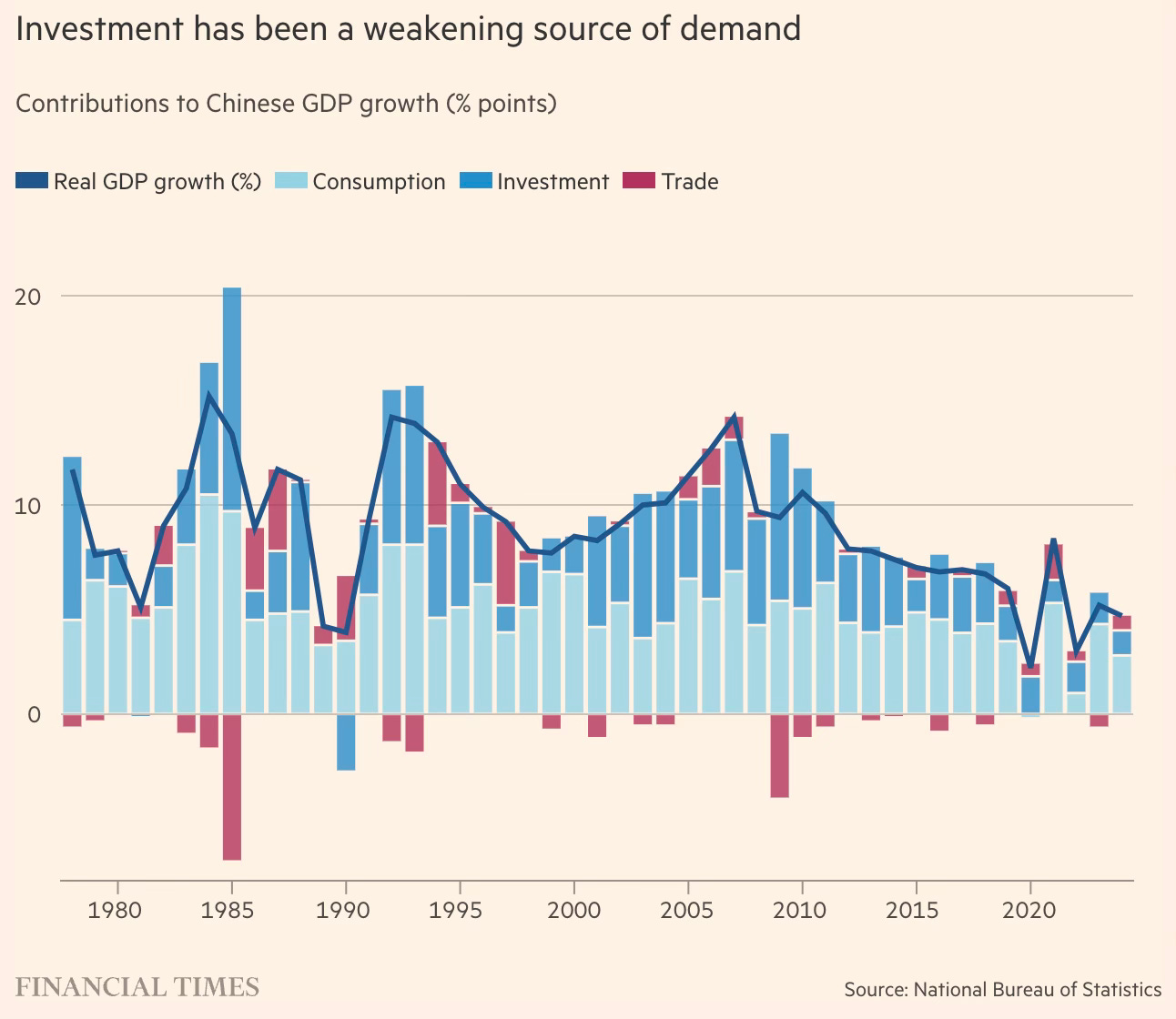

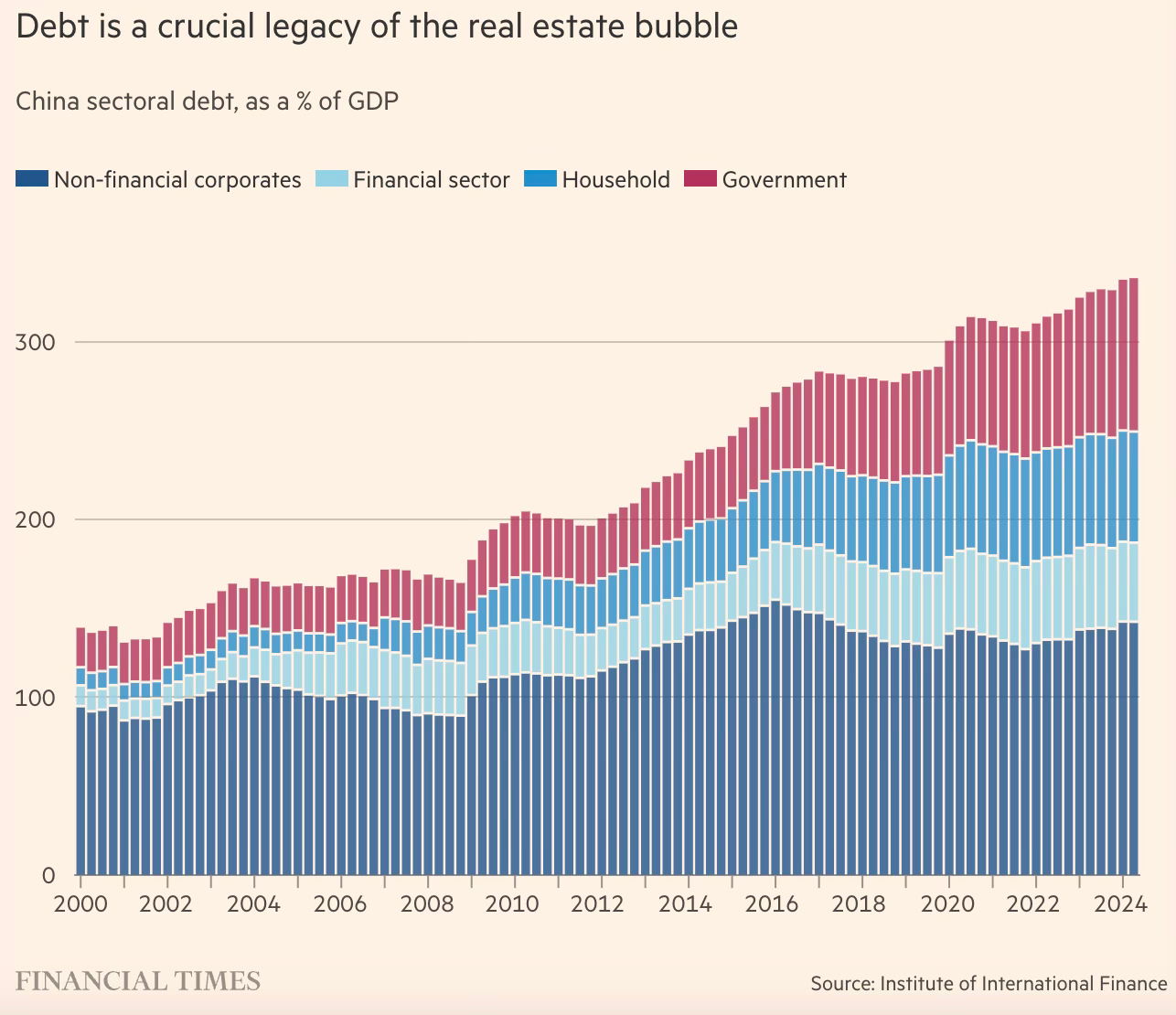

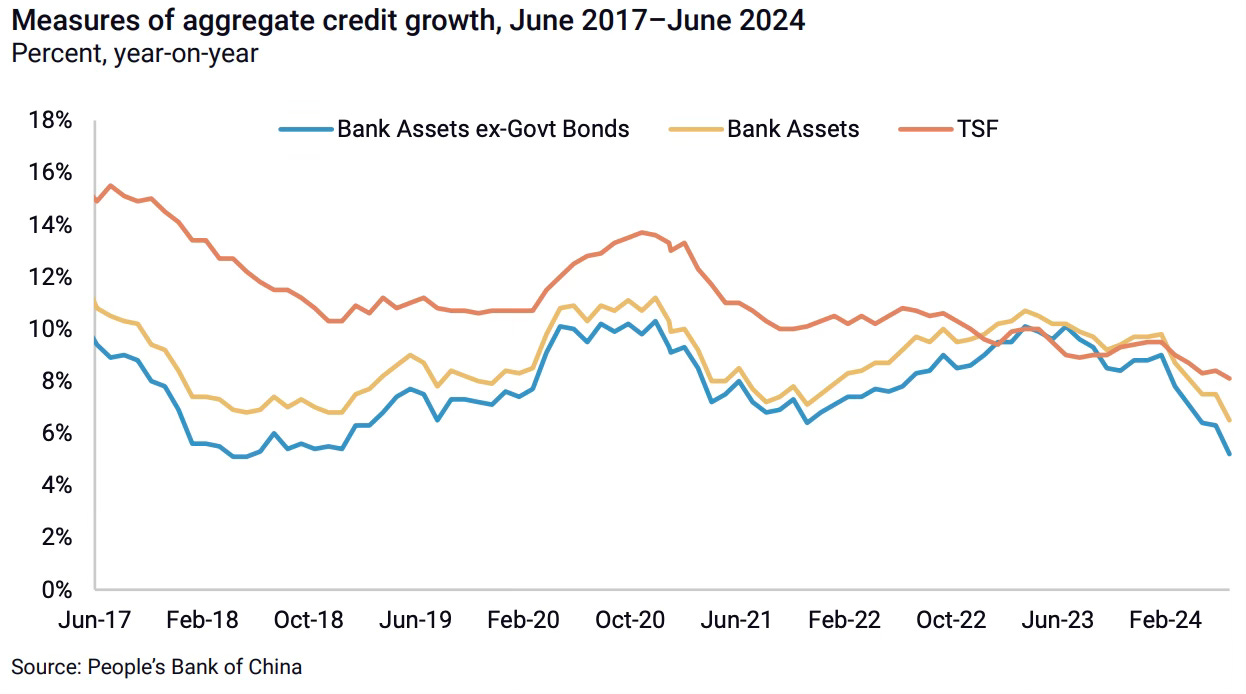

Its domestic policies artificially suppress business costs and give its firms an unmatched competitive advantage. Its financial repression keeps the cost of capital suppressed, the hukou system has depressed wages, and intense competition by local governments has kept land and utility costs low. Add to this all the direct state support of the kind mentioned above and the massive economies of scale, and it becomes almost impossible to compete with Chinese firms. Further, the scale and scope of these subsidies have allowed even loss-making firms to expand production and flood the market at deeply discounted prices.

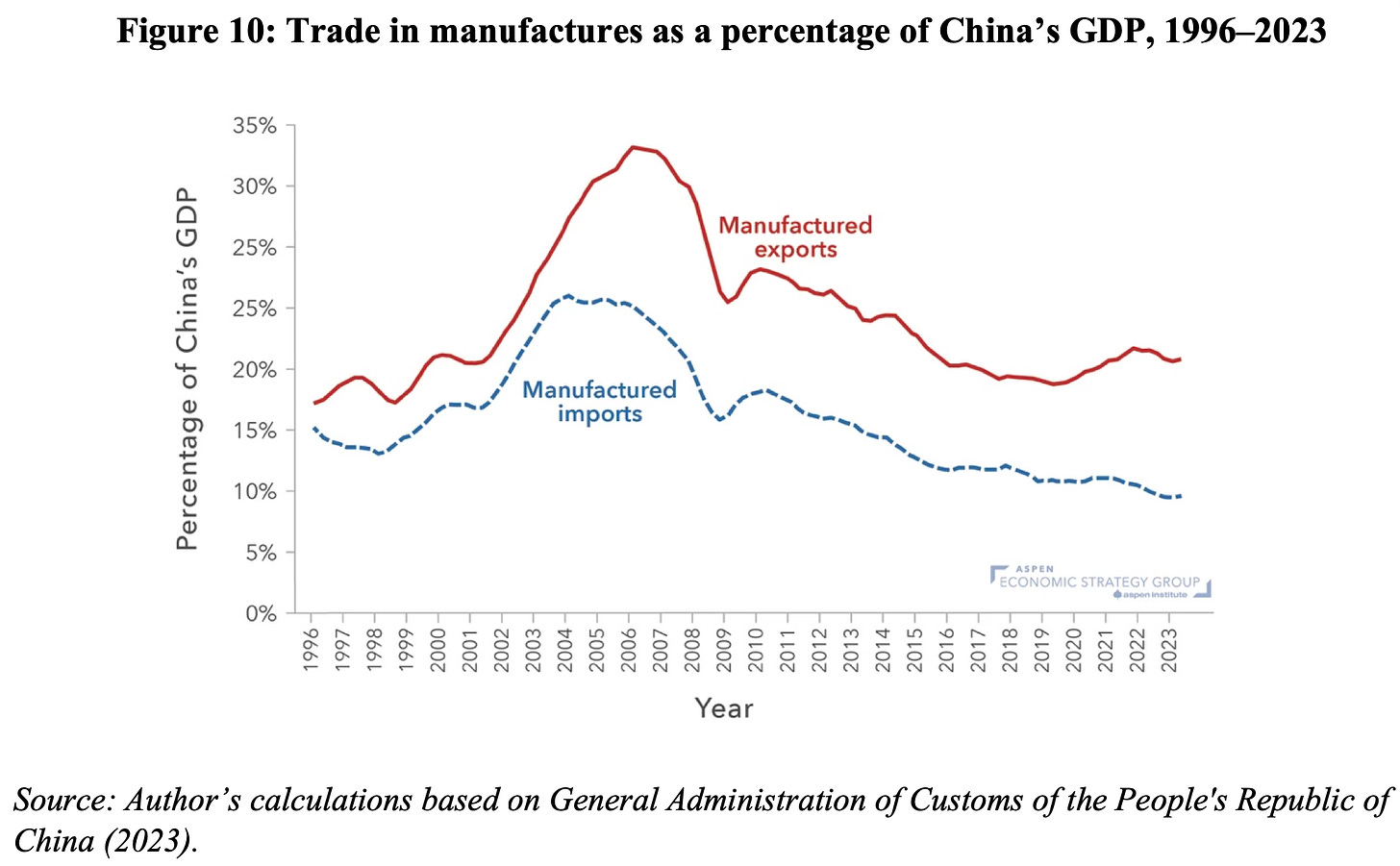

Accordingly, Chinese firms have built up production capacities in steel, cars and electric vehicles, EV batteries, solar panels, metro railways, heavy equipment etc., that are far in excess, often in multiples, of domestic demand. In many of these sectors, they make up 50-90% of the global production capacity. Finally, with the domestic economy slowing and demand weakening, these firms have come to rely even more on exports and further discounting to capture foreign demand. There cannot be any doubt that China’s excess capacity and discounted sales that render its trade partners uncompetitive should be treated as “prohibited subsidy”.

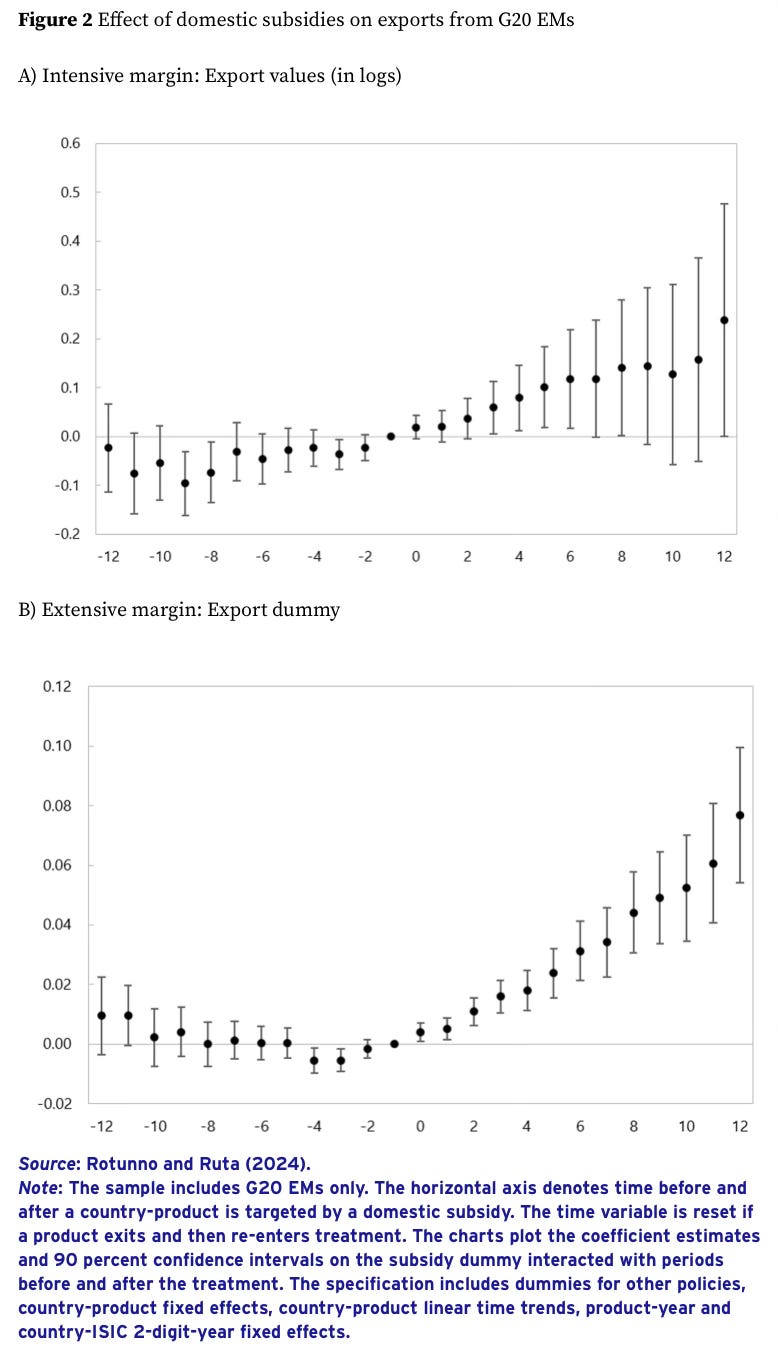

In this context, two IMF papers by Lorenzo Rotunno and Michele Ruta examined the trade spillover impacts of domestic subsidies generally and specifically by China. They quantify the significant impact of domestic subsidies on exports from G20 EMs. Exports of subsidised products increased for eight years since its introduction relative to exports of other products, whence the growth rate of exports of subsidised products is 15% higher. Similarly, at extensive margin (new products being exported), domestic subsidies increase the probability of a new product being exported by 3 percentage points relative to other products.

They also quantify the impact of Chinese subsidies.

Our results point to significant effects of China’s subsidies on its trade flows. On the export side, exports of subsidized products are 0.9% higher (relative to non-subsidized products) after China’s subsidies… This average effect masks significant heterogeneity across destination markets and sectors. Our estimates suggest that exports of subsidized products from China to other G20 emerging economies (G20 EMs) are 2.1% higher after the subsidy than exports of other products to the same destinations. Furthermore, the export effects of China’s subsidies vary considerably across sectors. Within electrical machinery – one of the new ‘strategic’ sectors – for instance, exports of subsidized products are found to be 7% higher than exports of other products after China’s subsidies.

On the import side, China’s subsidies are found to depress imports of targeted products relative to imports of non-subsidized products – an effect that is not found for other countries. Across origin countries, the implied effect on imports of subsidized products is stronger for Advanced Economies (AEs) – a 3% and 4.8% decrease in imports of subsidized products from G20 AEs and other AEs, respectively. Electrical machinery and metals are among the sectors where China’s subsidies have strong import-substitution effects. Our estimates therefore suggest that China’s subsidies have increased the country’s share in export markets and reduced its share in import markets of subsidized products.

The effects of China’s subsidies are amplified by supply-chain linkages… the exposure of downstream sectors to subsidies in upstream industries (through cost shares) and the exposure of upstream sectors to subsidies in downstream industries (through sales shares)… The results reveal strong effects of subsidies propagating from upstream industries. More subsidies given to supplying industries are associated with higher exports in the buying industry… consider the case of subsidies provided to the steel industry, which is the main supplier of inputs to the automotive industry (10 % of its total costs). The empirical results imply that increasing subsidies to steel by the number observed over 2015-2022 is associated with a 3.5% increase in exports of autos from China. These indirect effects are concentrated on exports to G20 AEs. The findings on the indirect effects of subsidies are consistent with upstream industries expanding supply and lowering their prices following the deployment of subsidies. This upstream effect allows industries downstream to become more competitive in export markets. Results from import regressions point to a negative effect of upstream subsidies on imports in downstream sectors. This result suggests that upstream subsidies allow downstream industries to also expand domestically and substitute for imports.

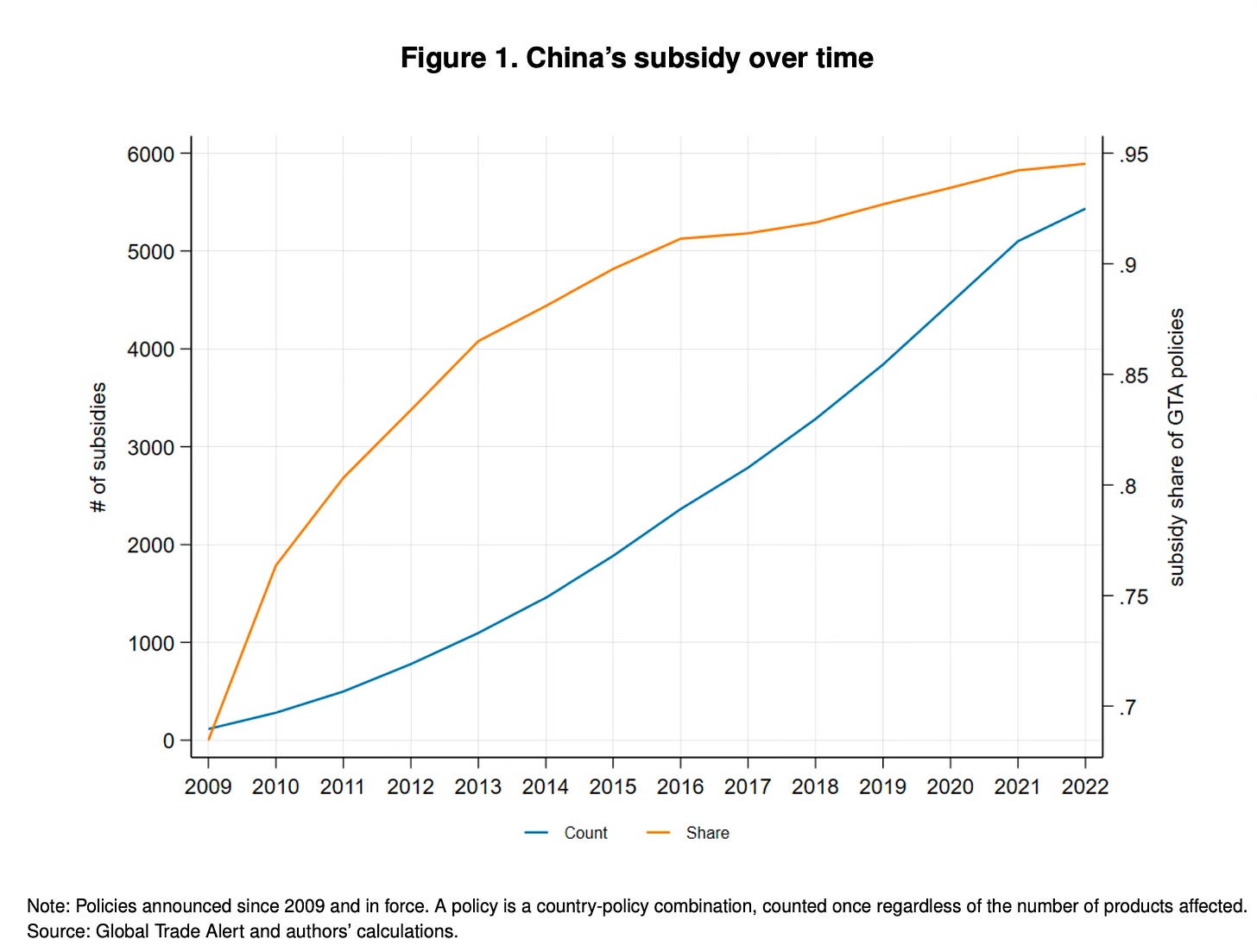

Subsidies form the overwhelming share of Chinese industrial policy instruments, representing 95% of all trade-distorting policies implemented in the 2009-22 period. This compared with 60-65% for other emerging economies in G20. Further, 98% of subsidies are monetary transfers to firms - state aid and grants.

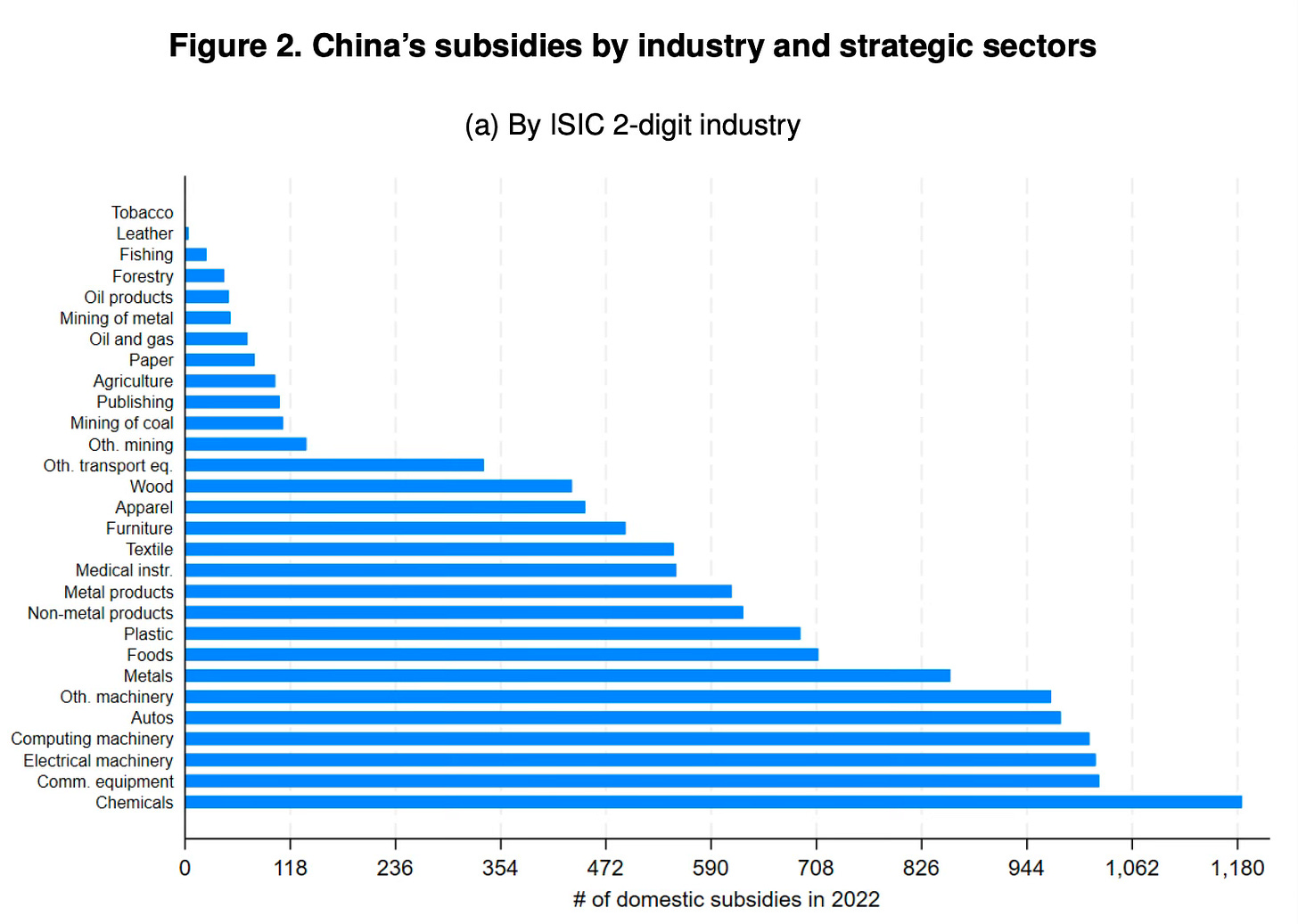

Chinese subsidies are focused on the manufacturing sectors.

The significant impact of domestic subsidies on exports in general (for all subsidising countries) and the especially higher impact of domestic subsidies observed in case of China is a reminder on the limitations of the SCM Agreement and WTO provisions in containing trade-distorting subsidies. As industrial policy interventions proliferate and as China exports its excess capacity aggressively, fixating on a narrowly defined set of subsidies that are “contingent on export performance” is meaningless. Other trade-distorting subsidies are allowed to expand without infringing on any WTO provision.

This is a matter of great significance for developing countries like India with limited fiscal space to provide subsidies at anything remotely close to China, and also especially because the Chinese subsidies are having a greater impact on exports to G20 EMs and imports from them.

As it seeks to expand its manufacturing base, India faces an onerous challenge across sectors. Competing with Chinese manufacturers requires significant levelling of the playing field to balance the massive subsidies that its exporting firms receive. This may no longer be confined to competition with exports coming directly out of China, but even those from countries like Vietnam. As FT reports, Vietnam is rapidly becoming an off-shore site for Chinese manufacturers, fuelling a third of all new investments in the country.

India’s industrial policy response has been to support its domestic manufacturers with its own subsidies, mainly through the PLI scheme and Basic Customs Duty (BCD) tariffs on imports.

But this has its limitations for at least two reasons. One, given the extent of the competitiveness gap, these subsidies and tariffs may not be adequate in many industries. Two, shorn off the BCD support, Indian firms fall behind even further in the export markets.

The first can be bridged to some extent by increasing the domestic value addition. This can help domestic manufacturers lower costs and increase their competitiveness. However, given the limited component manufacturing ecosystem, this can only be done in a phased manner. A possible strategy in this regard would be to target a handful of products with high domestic demand volumes and double down on the creation of a component ecosystem, thereby maximising domestic value addition. It might be required to provide a higher level of incentive than currently provided under the PLI for products to encourage component ecosystems to relocate. Once a critical mass of the component manufacturing ecosystem emerges, it may become possible to expand the base faster.

The second point on levelling the playing field on exports is equally important. Like maximising domestic value addition, another channel to improve the competitiveness of Indian manufacturers is economies of scale. Here, the small size of the Indian domestic market is a problem. For all its population size, India does not have the domestic market size to be able to generate the scale of demand required to reap the benefits of large economies of scale in most export market segments. This means that capturing export markets is an essential requirement. But the competitiveness gap is even higher in the export markets.

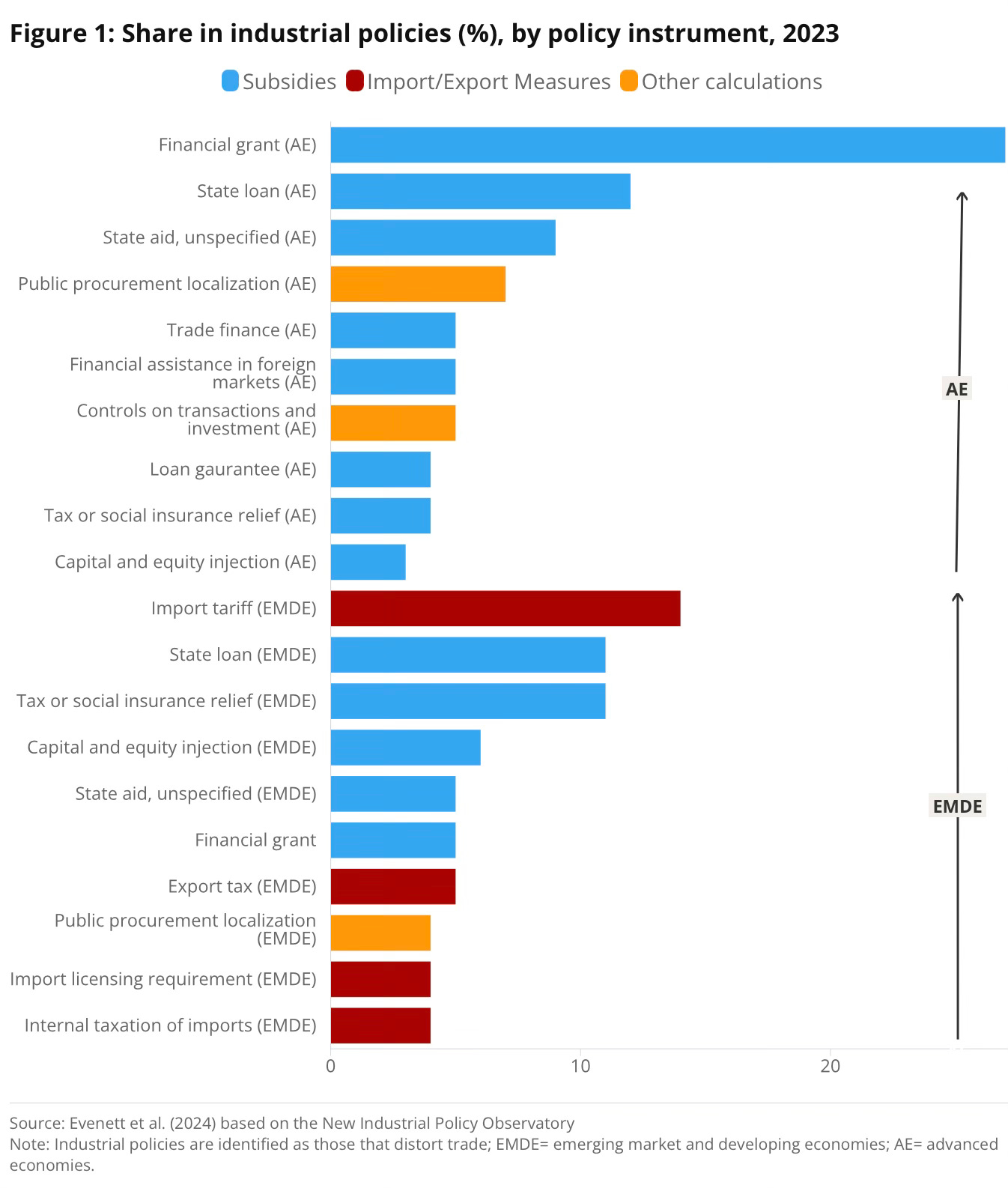

It is, therefore, essential that these domestic firms have some form of export subsidies. An option is to provide a higher level of incentives such that they are enough to match the competitiveness gap after excluding the BCD. But that would require a higher fiscal allocation and would also entail giving excess incentives for domestic sales. Another option would be to provide concessional trade finance or reimburse taxes on exports. Other instruments from the Table above could be considered.

In conclusion, for domestic industrial policy to be effective in expanding the domestic manufacturing base, it must necessarily include both some form of import protection and export incentives. Notwithstanding their WTO commitments, this choice is unavoidable for any country.