1. Debashis Basu writes about the case of C&C Towers Ltd (CCTL), the latest example of the unholy nexus between bankers and businessmen that has resulted in socialised losses.

It had signed a 20-year concession agreement with the Greater Mohali Area Development Authority (GMADA) in April 2009 for an inter-state bus terminal (ISBT), three multi-storey towers with retail and office spaces, a multiplex, a five-star hotel, a banquet hall, hypermarkets, and a helipad on top of one of the towers. The project turned bankrupt and went into liquidation, and was admitted for debt resolution. On October 19, the Chandigarh Bench of the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) passed an order... against an admitted claim of over Rs 579 crore, the resolution plan could provide for only Rs 81.5 crore, or just 14.08 per cent... The moment CCTL bagged the large multiplex project, it immediately gave an advance of Rs 110.78 crore as pre-construction advance and Rs 63.30 crore as mobilisation advance to a group company, C&C Construction Ltd (a listed firm which is also bankrupt). As always, a bunch of public-sector banks sanctioned money in November 2010. CCTL also collected Rs 490 crore from 400 property buyers. Construction was inordinately delayed, leading to the GMADA issuing termination notice in April 2016 and invoking bank guarantees of Rs 11.90 crore. A corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) started on October 10, 2019...

Consider these details of related-party transactions. CCTL had extended an advance to the extent of 35 per cent of the contract price to C&C. The transaction auditor has pointed out that the general business/industry practice is to advance 15-20 per cent of the contract value. As much as Rs 25.93 crore of the advance is still unadjusted against construction. CCTL had also made an excess payment of Rs 40.87 crore to C&C over and above the bills and mobilisation advances allowed. No lender approval had been sought for this payment, said the NCLT order. According to the terms of the contract, CCTL had the right to impose and levy liquidated damages of 0.25 per cent of the contract value per week or part of a week, a maximum of up to 5 per cent of the total contract value, ie Rs 15.82 crore in the case of default by the contractor (C&C). The work was scheduled to be completed within 18-30 months from December 16, 2009, for the ISBT and the hotel & commercial complex. Despite inordinate delay, CCTL has not imposed liquidation damages on C&C.

Basu is spot on in his assessment,

The CCTL promoters crafted a contract to drain substantial amounts of money and got away with it. The bankers and “independent engineers” of the GMADA did not monitor the project and did nothing to prevent money from being drained off to group companies. They are primarily responsible for this fraud, but they too got away... What were the bankers doing? What were the engineers of the GMADA doing? The answer is crystal clear in all such bankruptcy cases (especially in real estate involving public-sector banks), but it is one that we don’t want to see: Rampant fraud and corruption by everybody involved... The source of humungous bad loans that are written off periodically has nothing to do with poor bankruptcy laws, as claimed by bankers, such as Arundhati Bhattacharya, former State Bank of India chairperson. Yet, there is widespread opposition (even articulated by former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan) to criminal action against bankers because they would like to label these normal “business failures”.

Solutions like IBC and privatisation of banks without addressing fundamental issues of governance and political economy are like band-aid policies.

2. Interesting that the technology companies have laid off more people in India this year than all but the US! And layoffs among startups in India this year has already exceeded that for the full of last year.

This hiring winter comes even as Infosys and Wipro which together hired 208,000 graduates last three years have announced that they'll not be hiring this year. This is the first time since 2008 that any of the big Indian IT firms have not hired.

3. China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is at a crossroad.

The decline in investments has also been accompanied by rising criticism and domestic opposition in BRI countries, even as those countries struggle to repay the loans.

The best example is Pakistan where projects worth $62 bn have been committed. But 40% of projects have run into problems of corruption, cost overruns, funding shortfalls or adverse environmental impacts, and 20% have been cancelled or delayed indefinitely.

The current problems should also not take away from the scale at which BRI was done and its unprecedented promise.

Recipient countries such as Pakistan find themselves able to finance projects they could never have dreamt of under old-style foreign bilateral or multilateral aid programmes, from power plants to high-speed data networks... “In some senses, it was an absolute game changer,” says Bilal Gilani, executive director of Gallup Pakistan, a consultancy. He added that China was bringing in almost as much foreign investment into energy alone than “what Pakistan received as FDI in total in various sectors in 25 years prior to CPEC”. Hussain, the Pakistani senator, goes further, saying infrastructure on this scale was inconceivable in the country prior to BRI. “The only two projects which we have successfully done with a certain sustainability, with a certain perseverance, with a certain determination — one was the nuclear bomb . . . and the second is CPEC.”

A big problem has been the absence of private sector linkages. The Chinese have avoided seeing BRI as an economic investment opportunity. Instead, they have followed the model of lending, contracting, and supplying, thereby multiplying the value capture from the loans and limiting local spillover benefits.

“[We hoped] to get some Chinese companies to invest in Pakistan, in our special economic zones and then to export,” says a former Pakistani official, who declined to be identified. “That never took place. It’s OK to borrow money and build infrastructure, but it’s more difficult to bring investors into our zones to make stuff and sell it.” This lack of follow-through from Chinese private companies has arguably been CPEC’s biggest shortcoming. Analysts say that few Chinese businesses have shown an interest in setting up factories there, depriving the Pakistani government of the foreign currency earnings needed to service its non-rupee borrowings.

4. Livemint points to the annual survey of Indian cities by Janagraha and has some interesting graphics. This on the human resource deficiencies of Indian cities

This on the the low degree of devolution of powers to municipalities.

This on how poorly paid municipal councillors are.

5. Tell-all memoirs by senior government officials like

this do a lot of dis-service. Most often, as in this case, it's driven by personal agendas and egos. If that's not bad, it immediately increases risk-aversion in already risk-averse governments.

Senior bureaucrats earlier too used to write their memoirs. But there are three differences. One, their memoirs used to be atleast some years after their retirement. Two, even when it came out, it avoided controversial topics and playing to the galleries. Three, these memoirs used to be dignified accounts.

6. Some snippets on the emerging trends with the Indian economy.

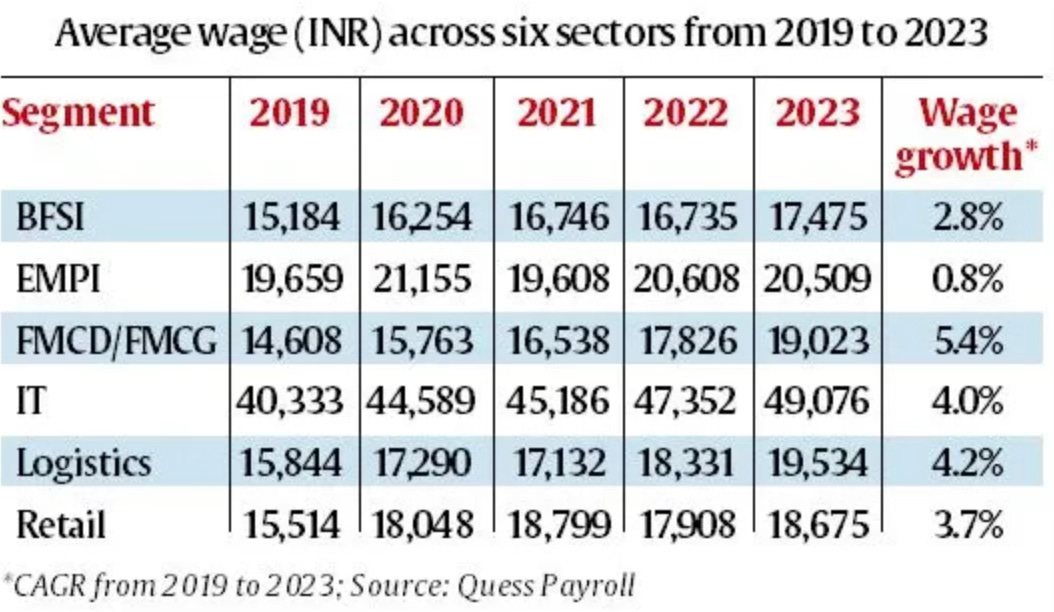

Sample this about wages

Real wages of casual wage workers in agriculture shows a negligible growth of 0.1% per year compared to the wages in 2019. For non-agricultural wages, they are yet lower than the level in 2019, with a decline of 1.1% from a year earlier... The situation for regular workers is no better... The latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) gives their earnings in 2022-23. Still, they fare worse, with real earnings remaining lower compared to the pre-pandemic levels. For the April-June quarter, real monthly earnings of regular workers have declined 0.5% per annum compared to their 2019 level. This is also true for the July-September quarter of last year, which shows real earnings decline at 1.6% per annum compared to their 2019 levels. But even compared to 2017-18, which is the year when the PLFS series begins, real earnings are lower for every quarter of 2022-23 compared to their levels in 2017-18. The decline is greater when compared to 2017-18, at an average 1.8% per annum.

This on a possible K-shape in the housing loans sector,

The housing loan interest rates before May 2022 had stood at 6.5-7%. Now they are at around 8.4% to 10%, with housing loan equated monthly instalments (EMIs) having jumped 20%. But this hasn’t slowed down their disbursal. Why? The answer lies in looking at the breakdown of housing loans between priority sector loans and the non-priority loans. Priority sector housing loans are defined as: “Loans to individuals up to ₹35 lakh in metropolitan centres (with a population of 10 lakh and above) and up to ₹25 lakh in other centres… provided the overall cost of the dwelling unit in the metropolitan centre and at other centres does not exceed ₹45 lakh and ₹30 lakh, respectively." The remaining loans are non-priority loans.

In the months leading up to May 2022, priority sector housing loans formed around 35-36% of the overall outstanding housing loans of banks. By June 2023, they had fallen to 31.5%, implying that banks are giving out more non-priority housing loans. Of course, these loans are largely taken on by the well-to-do, who do not get impacted much by the rise in EMIs. In fact, the outstanding priority sector housing loans of banks from January to June have been just 1-2% higher than during the same months in 2022. When it comes to non-priority housing loans of banks, they have been around 22% higher from January to June in comparison to the same months in 2022. Further, the percentages don’t explain this inequality well enough. The outstanding priority sector housing loans from June 2022 to June 2023 went up by ₹137.76 billion. In comparison, the non-priority sector housing loans went up by ₹2.47 trillion, nearly 17 times more.

And this about automobile sales in India.

Vehicle sales have been declining since 2018-19 and car and passenger vehicle sales have been nearly stagnant since 2011-12. The real growth in all categories happened from 2003-04 to 2010-11.

7. One of the intriguing things has been the stock market's calm reaction to geopolitical events like in the Middle East. But Ruchir Sharma points to historical data which appears to inform that the reaction now is par for the course.

In the days after the terror attacks in the US on 9/11, much cited as an analogue to 10/7 in Israel, America was on red alert for a follow-up. The S&P 500 fell by 12 per cent, the fall magnified no doubt by the fact that the US was six months into an eight-month recession. But that phase passed quickly — the S&P 500 would recover all its losses by October 11. The same pattern can be traced back much earlier. Looking at the stock market reaction to 25 of the most significant geopolitical crises since the second world war, including cross-border conflicts from Korea in 1950 and acts of terror from the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993, the S&P 500 dropped on average by around 4 per cent, reaching bottom in 15 days, but recovering fully in 33 days. Sixteen of these events took place in the Middle East or stemmed from conflicts or terror groups there — such as the bombings on public transport that hit Madrid in March 2004 and London in July 2005. After an initial impulsive sell-off, the market usually recovered the losses quickly. And the market sell-off on the latest conflict in the Gaza Strip is so far less striking than it has generally been. The bigger worry is rising interest rates.

We tend to overreact to present crises

The collective mind of the market, in contrast, recognises geopolitical risk as a historical constant, and frames fraught moments in that context. Is it clear, for example, that the Middle East is more precarious now than during any of the major conflagrations there since the second world war? That Russia is a more dangerous power after the loss of half its combat capacity in Ukraine? That China is a greater threat today, despite the steady weakening of its economy? The sum total of these threats is highly uncertain and debatable; the market, an aggregation of millions of views, is inclined not to rush to judgment. I met the legendary investor Julian Robertson in the late 1990s, when the hopes for world peace that followed the collapse of the Soviet empire were erased by new risks, including India and Pakistan carrying out a series of nuclear tests. Robertson advised me, as a young rookie investor, not to overreact.

This is a very wise article.

There's a natural propensity of humans to be more alarmed by their present and be blind to the long view. Are we really in a more fractured times? Is it worse than in 1972-73 or 1979, or earlier times of convulsions, especially during the peak of the Cold War? I'm being deliberately contrarian here.

8. On the implications of India's decision to ban on rice exports on the face of rising prices

By the end of July, India had banned exports of non-basmati white rice and followed this in August with a minimum sale price for basmati rice and a 20 per cent tariff on parboiled rice, extended until March. “It’s tough when a country that accounts for 40 per cent of global trade slaps a ban on half of what they export, and duties on the other half,” says Joseph Glauber, senior research fellow at food security think-tank International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and a former chief economist at the US Department of Agriculture... the benchmark rice prices in Thailand and Vietnam, the world’s second and third largest rice exporters, have risen 14 and 22 per cent since India imposed its ban. Arif Husain, chief economist at the UN World Food Programme, points out that the countries likely to be worst affected are already suffering from a litany of woes: sky-high food prices, soaring debt and depreciating currencies...

... countries in west Africa... are particularly exposed to India’s export ban, says the WFP’s Husain. In Togo, for example, almost 88 per cent of all rice imports came from India in 2022 and 61 per cent for Benin, the world’s largest importer of Indian broken rice. In Senegal, where 47 per cent of rice imports come from India...

The rice export ban is also important since over 40% of the global rice exports come from India.

The article points to concerns about global rice production going forward and its ability to meet the rising demand

Today’s predicament, analysts warn, is not so easily fixed. Fifteen years ago the world was not lacking in the grain, but that is no longer the case. The world population is set to reach close to 10bn by 2050 with the biggest growth in Africa and Asia. Researchers estimate this rise will increase demand for rice by almost a third, but yields are not keeping pace. After decades of rapid growth thanks to the development of new varieties, yields are stagnating in four big rice-producing countries in south-east Asia, according to a recent study in Nature Food, an academic journal. Globally, on average yields increased 0.9 per cent a year between 2011 and 2021, a slowdown from 1.2 per cent a year between 2001 and 2011, according to data from the UN.

The chief reason for this setback is climate change. Because rice grows in hot climates — 90 per cent of the world’s rice is produced in Asia — it is often assumed that a few extra degrees will not matter... This is not the case. Above certain temperatures, rice yields drop, explains Sander, adding that the grain is particularly sensitive to night-time heat. A 2017 study found that a global increase in temperature of 1C was likely to reduce rice yield by an average of 3.3 per cent. Temperatures have already risen by at least 1.1C since pre-industrial times. Modelling by commodity data group Gro Intelligence forecasts that by 2100, Asia’s top rice exporters will all experience a sharp increase in the number of days above 35C, with Thailand potentially seeing an 188 additional days above this threshold in a worst-case scenario. For Asia’s rice-producing deltas, from the Mekong to Ganges, climate change could present other complications. As temperatures increase, sea levels rise and salty water flows into fresh water rivers, irrigation channels and the soil, reducing yields or making growing impossible.

9. Parental income determines your SAT score in the US. Among SAT takers, the children of the richest 1% were 13 times and top 20% seven times more likely to score 1300 than children of the poorest quintile.

Given the low proportion of SAT takers among poor students, the disparity becomes even greater when we compare the ratio for all students who score more than 1300.

And the picture of the distribution of SAT score by income is even worse.

Born in sanctimony, nurtured with hypocrisy and sold with sophistry, ESG grew unchallenged for a decade, but it is now facing a mountain of troubles, almost all of them of its own making... If an asset is less risky, it should have lower expected returns. Thus advocates who argue that improving ESG will make firms less risky are directly contradicting other claims that investors will earn higher returns if they invest in high ESG companies. Adding an ESG constraint to investing will lower expected returns, with the only question being how much, leaving fund managers who have fallen for its charms in a fiduciary bind.

And he points to an unintended perverse consequence of the ESG fetish,

ESG pressures have led publicly traded fossil fuel companies to reduce spending on exploration and to divest fossil fuel assets, but private equity has filled the investment void. Is it any surprise that after trillions of dollars invested in fighting climate change, we are just as dependent on fossil fuels now as we were a decade or two ago?

11.

Rana Faroohar points to the latest UNCTAD report that highlights rising business concentration among exporters,

High levels of export concentration among the largest 2,000 firms globally increased during the pandemic. This was particularly true in developing countries, where data shows that the top 1 per cent of exporting businesses within each country received between 40 and 90 per cent of total export revenues for the nation as a whole. The median rate of corporate export concentration in a database of 30 developing countries is a whopping 40 per cent... The rise in corporate concentration has also mirrored the continued decline of labour share globally, which is down from 57 per cent in 2000 to 53 per cent today. As the authors put it: “The declining labour share and the rising profits of [multinationals] point to the key role of large corporations dominating international activities . . . [and] driving up global functional income inequality”.

12. Newspapers are reporting that Reliance is close to clinching a deal to buyout Walt Disney Co.'s India operations, Disney Star, at $7-10 bn. This would be a big coup for Reliance, coming on the back of pipping Disney Star to buy IPL rights for $2.7 bn and clinching a multi-year pact to broadcast Warner Bros Discovery Inc.'s HBO shows in India.

This of course raises concerns about India's media landscape and the control that Reliance would exert on it, over advertisers, content producers, and audiences.

13. India should refrain from pushing hard on IMF voting reform for now unless it has a good proposal with reasonable backing from others. As Alan Beattie has written here, any reform of IMF quotas in terms of voting rights proportionate to contributions or economic output is playing into China's hands and would leave India even worse off. He estimates that it would increase China'a voting rights from 6.4% to 14.1% and India's from 2.7% to 3.5%, a multiple of four compared to 2.25 now.

For now, replenishing IMF and WB's finances without change in voting pattern would be in India's interest. This is an area where India and US align perfectly.

14. Akash Prakash explains the perspective of foreign portfolio investors to the Indian equity market

The primary concern regarding India is its valuations. India is now, along with the US, the most expensive market in the world. Most allocators are naturally hesitant to commit capital with such high expectations already priced in. The most common questions remain on what can go wrong and what are we missing? What are the flaws in the India story? Some mentioned that we have been here before only for India to disappoint in the past. Why is this time different? My sense is that on any correction, a wall of money is waiting to come in, as few doubt the long-term potential of India. Every allocator we met was clear that five years from now they will have a lot more capital in India than they have today. While new investors are hesitant to commit capital today, most of the existing India investors are happy to live with the current valuations and keep their allocations largely unchanged. I heard the comment that India has always been expensive many times from this set of investors. There seemed to be no desire to take profits off the table in any significant manner.

15. Seven US tech companies not only dominate the US S&P 500 but also the global markets.

Seven large US tech companies have driven all of the gains in global stocks this year, pushing the US dominance of equity markets to new heights. The so-called “magnificent seven” — Apple, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, Alphabet, Nvidia and Tesla — have been propping up the S&P 500 index of blue-chip US companies for most of the year because of investor excitement about the growth of artificial intelligence. The trend has become so extreme that it is dominating markets abroad. But for the seven companies, MSCI’s benchmark All-Country World index of almost 3,000 large and midsized companies would have declined in the year to date, according to Bloomberg data. The seven have added almost $4tn in market capitalisation in 2023, compared with $3.4tn in gains for the MSCI index as a whole. They have added a combined 40 points to the index, which has risen 37 points overall. Unless there is a sharp turnaround by December, 2023 will mark the eighth year in the past decade that the US share of global market capitalisation has risen. US companies now account for 61 per cent of the $60tn index, compared with less than 50 per cent a decade ago. The largest 10 stocks make up almost 19 per cent of the index, up from 8 per cent in 2013.

This dominance has been accompanied by a rising concentration in valuations at the top in global equity markets.

16. I have blogged on multiple occasions about the need for startup businesses to establish their value proposition to build long-lasting businesses and not focus on scaling/growth for its own sake. Here's what

Nitin Kamath of internet stock brokerage firm Zerodha said while referring to his firm's valuation being "way higher than reality".

All of us on the core team have never thought of notional valuations right from the start because they can go up and down with market conditions. Focus on ever-changing valuations is a distraction... The focus has always been on building a resilient business, which means never having to rely on external capital.

17. Evoking memories of its crackdown on Jack Ma following his questioning of the government, China has cracked down on Foxconn

Two months ago, Terry Gou was talking big. Announcing his intention to run for president in his native Taiwan, Foxconn’s billionaire founder argued that China — home to most of the factories where the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer churns out Apple’s iPhones — could not touch him or his company. “If the Chinese Communist party regime were to say, ‘If you don’t listen to me, I’ll confiscate your assets from Foxconn’, I would say: ‘Yes, please do it!’ I cannot follow their orders, I won’t be threatened,” Gou said, insisting his business interests would not make him beholden to China. Now, Beijing has called his bluff on that boast. Tax inspectors have descended on Foxconn subsidiaries in two Chinese provinces and are investigating land use by group companies in two others, in a co-ordinated large-scale probe that Taiwanese executives and government officials say smacks of a politically motivated crackdown... His presidential bid has irked the Chinese leadership because it further fragments votes for Taiwan’s opposition and makes a victory for the Democratic Progressive party — which refuses to define the island as part of China — more likely, said a person close to Foxconn.

This might perhaps be the crossing the Rubicon moment for China's relationships with foreign investors. For decades, Chinese provinces and the central government have courted foreign investors. Foxconn in particular was especially feted. But now that Chinese companies have acquired enough expertise across the value chain of manufacturing in many sectors, Beijing feels that it can afford to arm-twist foreign investors who refuse to follow the Party line.