The Nobel Prize in Economics this year was awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt. I have blogged about his work here (why the Industrial Revolution happened in England), here (how expanded access to “technical literacy” promoted industrial development in Japan), here (useful R&D), and here (the importance of tinkering and microinventions).

This post will be about Mokyr, whom I have earlier described as arguably the most important and profound social scientist of our times. His work shines light on arguably the most important question of political economy: what drives economic progress?

Mokyr is best known for studying the period from the mid-eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, investigating the causes of the Industrial Revolution (IR) and its links to the Enlightenment, and showing that the causal link runs from the latter to the former. He argues that the latter fostered a belief in the possibility and desirability of human progress, scientific temper, and the culture of inquiry and problem-solving, all of which paved the path for the Industrial Enlightenment, which in turn, catalysed the conditions for the IR.

He first explained why the Enlightenment happened in Europe.

In Europe in 1500-1700, among the educated elite, there developed a culture and a set of institutions suitable for intellectual innovation and the accumulation of useful knowledge. Europe was lucky to stumble on an institutional solution that supported the market for ideas, actively encouraged innovation, and led to an exponential growth in useful knowledge. This institution was a transnational community of scholars, an intellectual commons resource (scientists, mathematicians, physicians, philosophers). It is described as the “commonwealth of learning” or the “Republic of Letters” (respublica literaria).

It was a virtual pan-European community that shared, distributed, and evaluated knowledge. It was the “community” that resolved the common resource (of new ideas) problem. Its rules included an open community, which excluded none and where knowledge and data should be shared; which was egalitarian and non-hierarchical; all knowledge, both old and new, was contestable (with no sacred cows); and all new propositions were to be reproduced, checked, tested, and evaluated (reliability of new knowledge).

The Republic of Letters created “open science” as a transnational intellectual commons management device. It created norms that new knowledge would be placed in the public realm and accessible to anyone who wanted to build on it and use it for technological purposes. By 1700, the norms of “open science” were fully in place. By creating a pan-European institution linking intellectuals, it also created economies of scale for ideas. Europe enjoyed “intellectual unification amidst political fragmentation”. It allowed new knowledge and discoveries to diffuse quickly into a large market.

The community thrived because it was largely independent of religion and politics. The political fragmentation of Europe, the Protestant Reformation, etc., limited rulers and organised religion from controlling knowledge creation. Those with ideas could shop around across kingdoms. Another contributor was patronage, which was a competitive market where sellers (those with ideas) and buyers (rulers, universities, academies, etc.) competed intensely to attract smart people to their court as a matter of prestige, and a source of getting useful advice, the latest medical care, tutors for their children, etc.

In simple terms, Mokyr showed that the most important institutional change that explains IR is not better property rights, a decline in transaction costs, or the Glorious Revolution in England. Instead, it was the institutions that governed the accumulation and diffusion of “useful knowledge” and the solution to the “knowledge commons” problem that the Republic of Letters in Europe provided.

Why did the IR start in Britain as opposed to continental Europe?

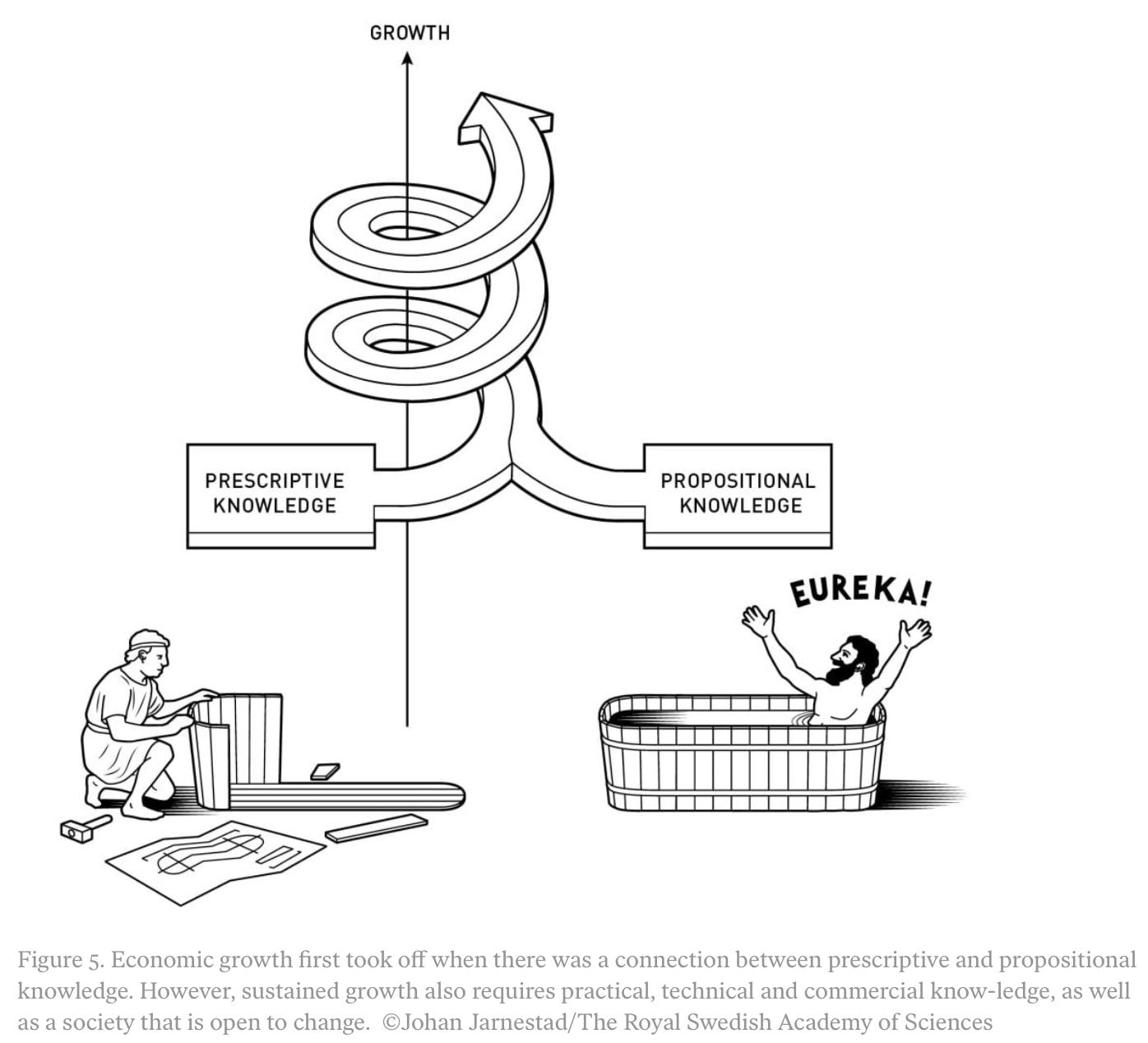

He uses the concept of useful knowledge to answer this question. He defines useful knowledge as that which promotes material progress. It consists of propositional knowledge (“what”) and prescriptive knowledge (“how”). The former describes the “regularities in the natural world that demonstrate why something works”, whereas the latter consists of “practical instructions, drawings or recipes that describe what is necessary for something to work”. It’s a distinction between people who know things (savants) and who make things (fabricants).

He described two aspects of the Age of Enlightenment that led to the deployment of useful knowledge to catalyse the IR and promote economic growth. One, the generation of useful knowledge by creating incentives (patents, awards, prizes, medals, pensions, memberships in Royal Societies, and generally higher social status, etc).

Second, easier and cheaper access to existing knowledge through written compilations like libraries, book indexes, alphabetisation, compilations based on topic, etc. The Age of Enlightenment expanded access by promoting the codification of knowledge and establishing linkages between philosophers, industrialists, entrepreneurs, inventors and artisans, etc. This meant that savants communicated not only with one another but also with fabricants.

All this created positive feedback mechanisms between propositional and prescriptive knowledge. He describes this fusion of scientific knowledge, technological know-how, and a culture that valued human progress as the Industrial Enlightenment.

The Industrial Enlightenment focused on material progress and the growth of prosperity, and it believed that useful knowledge was the key to achieving this. This became the Baconian program. While the English and continental European Enlightenment thinkers shared the belief in the possibility and desirability of progress, there was a crucial difference between them.

The continental enlightenment thinkers focused on morality, government, justice, and what was wrong with society. In contrast, the English intellectuals were less concerned with political and social issues, and more with the kind of progress driven by practical, useful knowledge leading to material advances. The English Enlightenment thinking concerned nuts and bolts, pulleys and belts, cogs and springs. As Roy Porter said, “British pragmatism was more than mere worldliness: it embodied a philosophy of expediency, a dedication to the art, science and duty of living well in the here and now.”

Supplementing this, in his classic work, The Culture of Growth, he points to the different ways in which cultural beliefs create the conditions for the adoption of technology.

The most direct link from culture and beliefs to technology runs through religion. If metaphysical beliefs are such that manipulating and controlling nature invoke a sense of fear or guilt, technological creativity will inevitably be limited in scope and extent. If the culture is heavily infused with respect and worship of ancient wisdom so that any intellectual innovation is considered deviant and blasphemous, technological creativity will be similarly constrained. Irreverence is a key to progress… so, as Lynn White has pointed out, is anthropocentrism. In his classic work, White stressed the importance of a belief in a creator who has designed a universe for the use of humans, who in exploiting nature would illustrate His wisdom and power… social attitudes toward production and work (and leisure) are another major factor in determining the likelihood of innovation.

Technologically progressive societies were often relatively egalitarian ones. In societies dominated by a small, wealthy, but unproductive and exploitative elite, the low social prestige of productive activity meant that creativity and innovation would be directed toward an agenda of interest to the elite. The educated and sophisticated elite focused on efforts supporting its power such as military prowess and administration, or on such topics of leisure as literature, games, the arts, and philosophy, and not so much on the mundane problems of the farmer in his field, the sailor on his ship, or the artisan in his workshop… The agenda of the leisurely elite was of great importance to the lovers of music in the eighteenth-century Habsburg lands, but was not of much interest to their farmers and manufacturers. The Austrian Empire created Haydn and Mozart, but no Industrial Revolution. As McCloskey has stressed, the bourgeois societies of the Netherlands and Britain of the seventeenth century, in contrast, were prime candidates for technological advances.

Finally, Mokyr’s work points to the importance of relentless implementation over just ideas. He describes microinventions, or the incremental improvements needed to turn a new idea into a significant product. Tinkering, embodiment, and scaling are examples of microinventions, and are often more important than the original breakthrough itself. Making technology useful often means building it at scale. Mokyr says,

“Most major inventions initially don’t work very well. They have to be tweaked, the way the steam engine was tinkered with by many engineers over decades. They have to be embodied by infrastructure, the way nuclear fission can’t produce useful electricity until it’s contained inside a working reactor. And they have to be built at scale, the way Ford’s Model T came down in price before it made big difference to the country.”

Interestingly, the Nobel Committee describes all three as “having explained innovation-driven economic growth”. I’m not sure that microinventions are exactly innovations, or what we commonly perceive as innovations. I’m inclined to argue that the popular narrative generated by the innovations and innovators in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector in the US over the last three decades has led to the diminution of persistence and implementation, and elevated ideas and eureka moments as the defining values and skills.

This narrative will most likely interpret Mokyr’s work as a nod to the importance of such innovation. But that may be misleading.

It should be noted that Mokyr’s examples of microinventions are tinkering, embodiment, and scaling. This is a process of continuous iteration and adaptation. I’m inclined to describe this as a process of innovation (a structured process of creating new or improved products) driven forward by improvisation (spontaneous, on-the-fly creation of solutions to an immediate problem). As Mokyr writes, for inventions to materialise, the latter may be more important than the former.

Extending this insight to the field of international development, I had blogged here.

The fundamental insight is that it’s not ideas that lead to development but their implementation, and that implementation is almost always far more daunting than the process of discovery of the idea itself. In fact, only a fraction of the pipeline of ideas ever finds its way into successful implementation… The most valuable individual and collective attributes for progress and development may be the desire and skills to tinker and embody (or institutionalise) to solve problems. In development in particular, they are far more important than the ability to ideate and innovate. Persistence and not mutation is what drives development (and much else in life)… It’s therefore apposite that development embraces and elevates the attributes, skills, and values of problem-solving through the process of tinkering, embodying, iterating, and scaling, instead of the current fetish with new ideas and innovation.

All in all, the Nobel to Mokyr is a recognition for arguably the pre-eminent social scientist of our times.