My column for Mirror/TOI Plus, the fourth in my series on trains in Indian cinema:

On the filmmaker’s birth centenary, a look at how the train is a motif in many of his films, including the Apu Trilogy, Nayak and Sonar Kella

|

| A still from Satyajit Ray's Nayak (1966), starring Sharmila Tagore and Uttam Kumar. |

Satyajit Ray, whose 100th birth anniversary was May 2, is associated with one of the most famous train sequences in all of cinema: The children, Apu and Durga in Pather Panchali, standing in a field of fluffy, white kaash flowers, listening for an oncoming train. I've always thought that what makes that sequence unforgettable is the rural Bengali landscape ruptured by the sound of the machine before the sight of it. The children hear the train's vibration in a pillar before the great beast rumbles past.

The

train remained a motif throughout the Apu Trilogy, acquiring more

layers of darkness with each film. What Ray had originally framed as

the link between the village and the city became, in Aparajito,

a marker of the distance between the two, and then in Apur

Sansar,

a site of potential death.

|

| The eternal train scene in Pather Panchali, Satyajit Ray's 1955 debut feature |

But there are two other films in which Ray put the train to less melancholic use. The first of these was Nayak, released on May 6, 1966, in which he cast real-life Bengali matinee idol Uttam Kumar as a film star called Arindam Mukherjee. When we meet Arindam, there are two items about him in the day's papers: One, a National Award he's being given in Delhi, and two, a brawl in which he was involved the night before. It's a succinct if simplistic summary of the film actor's life -- popularity and critical achievement, but alongside infamy.

Some mention is made of Arindam having left it too late to get a seat on a plane, and Ray thus successfully places his famed and shamed hero on a long train ride that exposes him to a microcosm of the Indian upper middle class – which, 55 years ago, was snootier about film stars than it is now. From the corporate head honcho who sniffs at the brawl to the old gentleman who disapproves of films on principle, the train isn't exactly filled with Arindam fans.

But

what really feels completely unreal in 2021 is the degree of

unguarded interaction that the train affords between the film star

and his public. Arindam is kind to little girls, signs some

autographs, and then gets drunk in a train toilet. When he stumbles

back to his compartment, the upper middle class housewife in it is

humane enough – and female enough – to help him to bed rather

than, say, take a picture of his disarray. Even the snarky journalist

(Sharmila Tagore) that Arindam ends up confiding in over a long

pantry car conversation, decides he is deserving of her humanity and

tears up her notes. The train serves, in many ways, as a filter –

Arindam is on display and yet somehow he isn't quite out in the open.

|

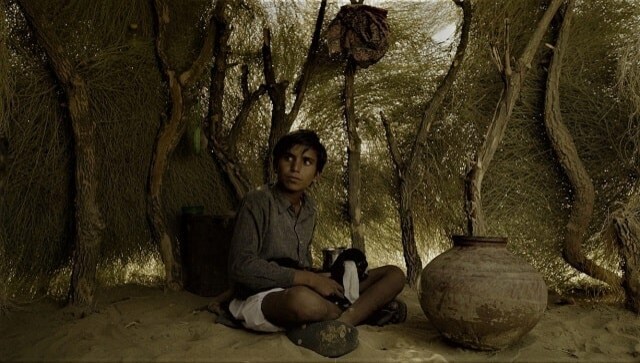

| On the sets of Sonar Kella (The Golden Fortress), 1974. |

But by far the most sprightly use of the train in Ray's cinema is in Sonar Kella (The Golden Fortress), the first film adaptation to feature his famously-popular detective, Feluda. Released in 1974, the whole film practically unfolds as a series of overlapping train journeys.

The very beginning of the adventure in Calcutta involves Feluda, played by the late Soumitra Chatterjee (who died after a battle with Covid in November 2020), silently removing from his bookshelf a hardbound copy of the Railway Timetable for November 1973. On the other side of events, we are introduced to the film's villains by being shown their names on a railway reservation chart: M Bose (Lower) and A Barman (Upper). Bose and Barman are hot on the trail of the originary set of train travellers – a six-year-old child constantly making crayon sketches of a past birth, and a parapsychologist taking him to Rajasthan in the hope of identifying the golden fortress of his drawings.

The train is also where Feluda and his nephew Topshe first meet the man who will become the third member of their trio: The mystery writer Lalmohan Ganguly alias Jatayu. He boards their compartment at Kanpur station with his red 'Japani suitcase... imported', and proceeds to speak several sentences in rather grandiloquent Hindi before realising that his companions are Bengalis, too.

It is a remarkably orderly world that Ray maps out, in which precise calculations can be made based on train timings. If a set of people hasn’t arrived at Jodhpur in the morning, they can be assumed to arrive by the evening train instead. And if the expected villains haven't shown up on the day they should have, Feluda speculates that they may have failed to get a train booking.

Trains in The Golden Fortress are the route to excitement, transporting these parties of Bengalis into the 'dacoit-infested country' of western Rajasthan. But trains are also the possible way back to order and civilisation: In one pre-climactic moment, Feluda offers Lalmohan Babu the option of getting off at Pokhran, from where he can catch a train back, rather than proceeding to Jaisalmer with them.

In

one of Sonar

Kella's most

memorable scenes, the intrepid Bengalis get on camel-back, and try to

wave a train down across the desert. It's the one time in the film

that Feluda's plan doesn't succeed. The train keeps on going.

Published in Mumbai Mirror (9 May 2021) & in TOI Plus (8 May 2021).