My Mumbai Mirror column:

In Mrinal Sen’s 1982 film Chaalchitra,

the filmmaker turns his astute gaze upon the smokescreen that is the business

of news in a capitalist world.

In 1982, Jyoti Basu, who was then the chief minister of West Bengal, watched Mrinal Sen's newly-completed film Kharij (‘The Case is Closed’), about a middle class family's attempts to pass the buck when their under-aged servant boy dies of carbon monoxide poisoning.

“The film is excellent, but it is too grim to be popular,” Basu had apparently said.

Sen didn't make only grim films, but he knew perfectly well what Jyoti babu meant. In 1981, a year before this incident, the great actor Utpal Dutt had played a newspaper editor in Sen's film Chaalchitra (‘The Kaleidoscope’). In a crucial establishing sequence, the pipe-smoking Dutt tells an idealistic young job seeker Dipu (Anjan Dutta) to come back in two days with an “intimate study” of his “middle class milieu”. His only instruction is to keep the tone light, because the piece must sell.

The big boss testing the potential employee is also the man-of-the-world lecturing the ingenue. Already, 40 years ago, in Sen's sharp-eyed vision, we see the media being clearly understood (by those who run it) in terms of the political limits placed on it by those who buy it – ie, the middle class.

When Dipu walks into the editor's grand office, he is hoping to escape a dull job elsewhere and clearly has a positive, perhaps even idealistic, image of the media. Asked to name an article he enjoyed reading in the paper in the recent past, Dipu enthusiastically mentions a feature about rickshaw wallahs. The editor is unmoved. “Yes, that piece gained some popularity,” he replies. “People are eating it up.”

“See, we've got to feed the public,” he says matter-of-factly to the young man who is his son's classmate. “Some sell potatoes, some bananas, some sell words. And we, we sell news. The whole goddamn world is one big shopping centre. And we're all pedlars.”

Chaalchitra didn't sell well, either in the commercial Bengali cinema market or in the film festival universe where Sen's films often found their niche. But it is an interesting film, not least for the historical reason that it is the only one of Sen's 25-odd films as a director, to be written by him. Dipankar Mukhopadhyay, in his biography of Sen, describes how the idea of it took shape. The incident Mukhopadhyaya describes as a creative trigger is oddly tangential to the film at hand. An old man arrived at Sen's doorstep one day, claiming to be his school friend from the village. Sen, who had come to Calcutta in 1940, couldn't remember the man's face or their acquaintance. But seeing that he had brought children with him, Sen finally feigned recognition. Still, when the family departed after having spent some time with Sen, he felt irritation that they had wasted his evening.

What the incident seems to have evoked for Sen is the distance he had travelled away from his roots. Two years before Chaalchitra, the filmmaker had acquired a car and moved to a posher locality. Chaalchitra was perhaps his last engagement with the lower middle class milieu he had left behind – and it is discomfiting in its honesty about the protagonist's decision to cut that cord.

Dipu spends the film searching for a 'story' amid the mundane details of his everyday life, a story that will get him the job. But although tensions erupt often, people seem keener to resolve them than to make them flare up further. The occupants of his chawl-like building in Shyambazar squabble over their dirty, mossy courtyard, but also get together to scrub it clean in a fit of anger. When one of the poorer old women in the building steals coal from Dipu's mother's bin, Dipu's mother takes care to safeguard it – but without a hue and cry about the theft. Even a fake astrologer that Dipu first thinks might make for an expose seems, upon reflection, a poor man in need of an income. Everything he observes has a flip side, a legitimate reason.

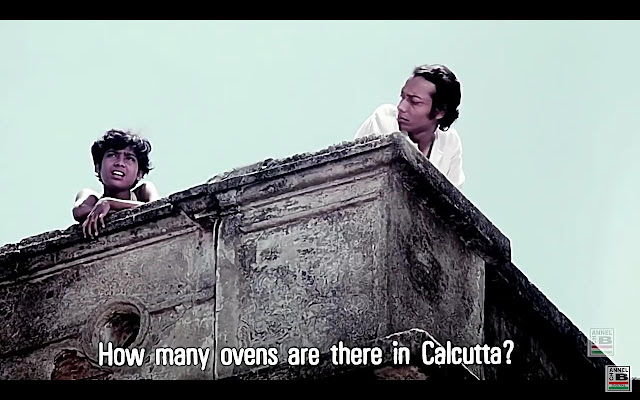

When he comes up with a story about the inescapable smoke from coal ovens in the city, the editor is excited – but wants to remove the flip side. Rather than question why the country's lower middle class still cooks with such fuel (the fact that gas ovens were -- and are-- too expensive), the editor believes what will sell with the middle class 'public' is a story about polluted air; the poison that they are forced to breathe. Does Dipu want to be a communist, or does he want the salary?

Earlier, in a remarkably edited sequence, Sen reveals how the same city that seemed so harsh when you're a poor man trying to hail a taxi in an emergency, turns into a tableaux of pleasures, seen from the back seat of a car.

The film ends with the arrival of the gas cylinder. It is only for Dipu's family, though -- leaving the rest of the building, the city, the country to continue in its haze of smoke. It's much thicker now.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 7 Feb 2021.