Hindi: chhoti haziri, vulg. hazri, 'little breakfast'; refreshment taken in the early morning, before or after the morning exercise. (Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, 1994 [1886])

3 November 2024

Warp & Weft of History: Mishal Husain's Broken Threads

I read the BBC presenter's Mishal Husain's family history and then interviewed her about it for this India Today piece:

28 May 2021

A child's view of the world through a train ride

This is the sixth column in my ongoing series on trains in Indian cinema. (Periodic reminder for new readers of this blog: I write a weekly column on cinema which appears in TOI Plus, as well as in Bangalore Mirror, Pune Mirror & Mumbai Mirror.)

-- In Gulzar's Kitaab, the railways are a route and a

rite of passage for a child trying to find his place in the universe --

There are probably few films in any language that have been titled 'book'. But lest you think a film called Kitaab might be bookish (which in the eyes of many movie-viewers translates to boring), Gulzar's 1977 screen adaptation of Samaresh Basu's story begins in breathless motion. Gusts of black smoke rise into the sky, a train whistles, and the familiar “chooka-chook” of the moving carriage takes over, interspersed with a child's voice. He is making up a chant to match the train's rhythmic sound: Kidhar ja, kidhar ja, kidhar ja? Bhaag chala, bhaag chala, bhaag chala [Where d'you go, where d'you go, where d'you go? Running away, running away, running away].

Unlike Siddhartha, though, the experience doesn't lead him to renounce the world – but to return to it richer. One could read Kitaab as a cop-out: Issuing a challenge to middle class pieties and normative barriers, but turning back before risk turns to danger. But one can also see it as an expansion of the child's universe, an initiation into life that acknowledges the inevitability of sorrow -- while not undermining the value of the safety net. As the blind train singer puts it, “Gaadi chhutne ka gham mat kariyo, baalak. Station na chhutne paaye [Don't mourn the missed train, child. Just don't let the station get away from you.]”

Published in TOI Plus, and three editions of Mirror -- Pune, Bangalore and Mumbai.

8 February 2021

What sells in the media hasn’t changed in 40 years

My Mumbai Mirror column:

In Mrinal Sen’s 1982 film Chaalchitra,

the filmmaker turns his astute gaze upon the smokescreen that is the business

of news in a capitalist world.

In 1982, Jyoti Basu, who was then the chief minister of West Bengal, watched Mrinal Sen's newly-completed film Kharij (‘The Case is Closed’), about a middle class family's attempts to pass the buck when their under-aged servant boy dies of carbon monoxide poisoning.

“The film is excellent, but it is too grim to be popular,” Basu had apparently said.

Sen didn't make only grim films, but he knew perfectly well what Jyoti babu meant. In 1981, a year before this incident, the great actor Utpal Dutt had played a newspaper editor in Sen's film Chaalchitra (‘The Kaleidoscope’). In a crucial establishing sequence, the pipe-smoking Dutt tells an idealistic young job seeker Dipu (Anjan Dutta) to come back in two days with an “intimate study” of his “middle class milieu”. His only instruction is to keep the tone light, because the piece must sell.

The big boss testing the potential employee is also the man-of-the-world lecturing the ingenue. Already, 40 years ago, in Sen's sharp-eyed vision, we see the media being clearly understood (by those who run it) in terms of the political limits placed on it by those who buy it – ie, the middle class.

When Dipu walks into the editor's grand office, he is hoping to escape a dull job elsewhere and clearly has a positive, perhaps even idealistic, image of the media. Asked to name an article he enjoyed reading in the paper in the recent past, Dipu enthusiastically mentions a feature about rickshaw wallahs. The editor is unmoved. “Yes, that piece gained some popularity,” he replies. “People are eating it up.”

“See, we've got to feed the public,” he says matter-of-factly to the young man who is his son's classmate. “Some sell potatoes, some bananas, some sell words. And we, we sell news. The whole goddamn world is one big shopping centre. And we're all pedlars.”

Chaalchitra didn't sell well, either in the commercial Bengali cinema market or in the film festival universe where Sen's films often found their niche. But it is an interesting film, not least for the historical reason that it is the only one of Sen's 25-odd films as a director, to be written by him. Dipankar Mukhopadhyay, in his biography of Sen, describes how the idea of it took shape. The incident Mukhopadhyaya describes as a creative trigger is oddly tangential to the film at hand. An old man arrived at Sen's doorstep one day, claiming to be his school friend from the village. Sen, who had come to Calcutta in 1940, couldn't remember the man's face or their acquaintance. But seeing that he had brought children with him, Sen finally feigned recognition. Still, when the family departed after having spent some time with Sen, he felt irritation that they had wasted his evening.

What the incident seems to have evoked for Sen is the distance he had travelled away from his roots. Two years before Chaalchitra, the filmmaker had acquired a car and moved to a posher locality. Chaalchitra was perhaps his last engagement with the lower middle class milieu he had left behind – and it is discomfiting in its honesty about the protagonist's decision to cut that cord.

Dipu spends the film searching for a 'story' amid the mundane details of his everyday life, a story that will get him the job. But although tensions erupt often, people seem keener to resolve them than to make them flare up further. The occupants of his chawl-like building in Shyambazar squabble over their dirty, mossy courtyard, but also get together to scrub it clean in a fit of anger. When one of the poorer old women in the building steals coal from Dipu's mother's bin, Dipu's mother takes care to safeguard it – but without a hue and cry about the theft. Even a fake astrologer that Dipu first thinks might make for an expose seems, upon reflection, a poor man in need of an income. Everything he observes has a flip side, a legitimate reason.

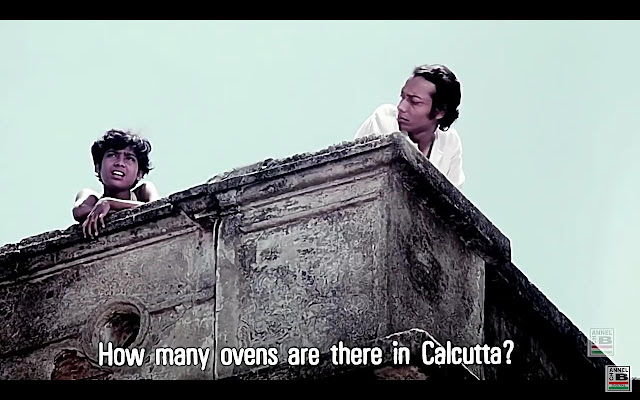

When he comes up with a story about the inescapable smoke from coal ovens in the city, the editor is excited – but wants to remove the flip side. Rather than question why the country's lower middle class still cooks with such fuel (the fact that gas ovens were -- and are-- too expensive), the editor believes what will sell with the middle class 'public' is a story about polluted air; the poison that they are forced to breathe. Does Dipu want to be a communist, or does he want the salary?

Earlier, in a remarkably edited sequence, Sen reveals how the same city that seemed so harsh when you're a poor man trying to hail a taxi in an emergency, turns into a tableaux of pleasures, seen from the back seat of a car.

The film ends with the arrival of the gas cylinder. It is only for Dipu's family, though -- leaving the rest of the building, the city, the country to continue in its haze of smoke. It's much thicker now.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 7 Feb 2021.

23 November 2020

In vino veritas – I

My Mirror column:

Jayaprakash Radhakrishnan’s deceptively simple film The Mosquito

Philosophy (2019) leaves you asking, who really are the suckers?

|

| A drinking session becomes a place for revelations in The Mosquito Philosophy (2019). |

About ten minutes into Jayaprakash Radhakrishnan's sort-of-mumblecore

Tamil film The Mosquito Philosophy (2019), a man complains to his

friend that the liquor shop overcharged him, but no-one in the crowd

supported his case against the cheating shopkeeper. “Do they have no

self-respect or guts?” Suresh mutters. “Well, it is to gain self-respect

and guts that we drink!” laughs his friend JP (played by Radhakrishnan

himself). “Don't expect anything from the men in a liquor shop until

they're high!”

It feels like a throwaway line, just

a bit of humour. But as we get deeper into the nightlong drinking

session that is the film's chosen milieu, we are made to realise that

alcohol does serve that purpose, among others. In fact, The Mosquito

Philosophy feels almost inspired by that old Latin proverb, In vino veritas

- In wine, there is truth. As an English poet called Abraham Fraunce

put it as far back in 1592: “Wine moderately taken maketh men joyfull;

he is also naked; for, in vino veritas: drunkards tell all, and sometimes more then all.”

The

four men have met because Suresh has some news that deserves a

celebration. The only single one in their group, he’s finally decided to

get married. But he is just a little cagey about telling his friends,

and it soon becomes clear why: he has sworn for years that he would only

have a love marriage. Now, at forty, he has made a decision to accept

an arranged marriage prospect. It's all to make his mother happy, he

insists – and then it turns out that the girl chosen by his mother is

fifteen years his junior.

What makes the film

successful is its quality of creeping up on you, rather than bombarding

you with the things it wants you to think about. The predictable wife

jokes at the start ease the viewer gently into a familiar middle class

Indian milieu dominated by them. “Oh don't worry, no wife thinks her

husband's friends can ever be a good influence,” says JP, and over the

course of the film, each man in turn gets mocked for being afraid of his

spouse. “Suresh, that's life after marriage,” the friends say to the

soon-to-be-married man when one of them rushes back home to eat because

his wife hasn't given him permission to be out for dinner.

JP

seems the best adjusted of the men with respect to his wife – she is in

and out of the room while his friends drink, and even joins in the

conversation occasionally. But he has also asked his friends over for a

drinking session without first checking with her - if he asks her first,

he chuckles to Suresh, she is likely to refuse. Again, it's a throwaway

moment – but it finds a larger echo when we hear over the course of the

evening that JP followed his wife around for nine months before she

agreed to marry him. What he describes as a college romance, a drunken

Suresh now points out, could well be understood as stalking – JP simple

didn't take no for an answer.

Is there is something

worrying about a world in which husbands must ask their wives'

"permission" to go have a drink or hang out with their friends? Yes, but

there is also something worrying about a world in which a

twenty-four-year old woman finds herself in the position of accepting an

arranged marriage with a not-particularly-attractive man over fifteen

years her senior. There is something particularly sad about the fact

that a man who isn't even married already feels put upon, not excited,

when his fiance calls him to make weekend plans.

"Truth is

like fire, it glows and burns," Suresh quotes the artist Gustav Klimt as

having once said. The scalding truth of this society is that men and

women continue to look at each other as separate species, each brought

up to perceive the other as a creature that needs to be tricked into

captivity -- not lived with in mutually defined freedom. It is no

coincidence that even the alcoholic haze that lets home truths be spoken

is closed off to one gender.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 15 Nov 2020.

25 October 2020

The doctor as sufferer

My Mirror column, sixth in my series on films about doctors:

Based on AJ Cronin’s famous 1937 novel The Citadel, Vijay Anand’s medical melodrama Tere Mere Sapne (1971) casts doctors as the ailing ones

Like several of the films I've written about in recent weeks, Vijay Anand’s Tere Mere Sapne (1971) had as its protagonist not a doctor, but the medical profession itself. And thus, perhaps necessarily, several doctors. The director's brother Dev Anand may have supplied the film's star quotient (as the rather unimaginatively named hero Dr Anand), but within the film's opening ten minutes we meet three other doctors. These are the characters that actually give us the lay of the land

First up is Dr Anand's medical batchmate, who delivers the first line of dialogue in the film: “Jise tum aadarsh kehte ho, usse main paagalpan kehta hoon [What

you call principle, I call madness].” He suggests establishing a

moneymaking practice in the city together, but the idealistic Anand

mocks him for being a businessman instead of a doctor - and leaves for a

remote mining village. The second doctor we meet is the ageing Dr

Prasad (the marvellous Mahesh Kaul), employed by the mining company for

35 years, but now so ill that he hires younger doctors as ‘assistants’

to work in his stead - while his paranoid wife attempts to keep his

illness a secret. The third doctor is also interesting: Dr Prasad’s

other assistant, one Dr Jagannath Kothari, played by Vijay Anand

himself. A gynaecologist with a fancy degree from London, Jagan now

spends most of his waking hours drinking himself into a stupor.

What

is common to these very different characters – and what eventually

comes to drive our hero as well – is money, or the lack of it. The

idealists are led by the old Dr Prasad, who has spent a

lifetime in the service of poor mine workers, but without being able to

realise his dream of improving the medical facilities in the area. The

unruly-haired Dr Jagan, meanwhile, is only on his way to middle age, but

already embittered by the bureaucratic and other restrictions that kept

a young doctor from rising in a socialist India [these are complaints

about the system that continued to appear in later films I’ve written

about, like Bemisaal (1981) and Ek Doctor Ki Maut (1989)].

Our hero arrives in the village full of reformist zeal, initially even

managing to rouse Jagan out of his alcoholic self-pity - but his honesty

and hard work are of no avail either in his career, or when he finds

himself up in court against a powerful rich man.

Thus

the corruption of the system – and we’re talking 50 years ago – is

blamed for Dr Anand’s moral decline. Which is how the film leads us back

to the first doctor it showed us, the one who has no compunctions about

using his qualifications as a way to mint money. In the second half, it

is his network of fashionable city doctors catering to the rich and

famous that an angry Dev Anand becomes part of. “Aaj tak mere aadarsh hi meri daulat thhe, lekin aaj se daulat hi mera aadarsh ban jayegi

[Till today my principles were my wealth, from now on wealth will be my

principle],” he announces to his increasingly distressed wife Nisha

(Mumtaz).

There are many

things that relegate this film to its time: the paternalistic take on

mine workers as easily misguided/corrupted; the dismissal of the village

midwife as necessarily knowing less about delivering a baby than any

doctor – even one not trained in gynaecology; the portrayal of Dr Prasad

as the generous, open-hearted idealist at the mercy of a small-minded,

penny-pinching wife.

But despite these, within its melodramatic dialogue-baazi, something still rings true. And again, as in Anuradha, which I wrote about last week, it is only a doctor who can manage to get through to another doctor. This is true of the pre-climactic scenes, featuring Dr Anand’s restoration to the milk of human kindness. But Tere Mere Sapne’s most moving scene might be between the ailing Dr Prasad and Jagan, his black sheep doctor employee. “Does such a capable doctor not recognise his own symptoms?” asks Jagan. And when the old man says he does, but has decided to wait for death, Jagan’s response is: “Yeh ek mareez baat kar raha hai, doctor nahi. [This is a patient speaking, not a doctor.]” This exhorting of the doctor to a special status recurs through the film, as for instance when a famous actress (Hema Malini in a fetching part) tells Dev Anand to cheer up because “if a doctor speaks like this, what will the patient do?”

The doctor in Hindi cinema, it seems, must not only carry the god-like mantle of giver of life, but hide his own emotional travails. The mantle is a veil.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 25 Oct 2020.

19 October 2020

The Doctor as Anti-Hero

My Mirror column (this is the fourth piece in my series on doctors in our films):

Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Bemisal (1982) can be viewed as

a subtle, affecting love triangle, but it is also a rare Indian film

about medical malpractice -- and the possibility of atonement.

Bemisal opens with a man in a kurta-pajama cycling between villages, with only a sola topi to protect him from the sun. From the little box affixed to his cycle, one wonders if he is a postman, but the mystery is solved soon: he is a doctor. “The only doctor within a forty mile radius,” as we learn when he gets home for a minute, only to be called away again before he can lunch with his wife.

This vision of the doctor as he should be, or at least could be – a much-needed saviour of the Indian poor – is one of the two faces of the medical profession in Hrishikesh Mukherjee's 1982 film. And ostensibly Vinod Mehra, as Dr. Prashant Chaturvedi, plays both of them.

A Hindi adaptation of the Bengali film Ami Se O Shakha, Bemisal relocates the writer Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay's original tale of friendship and sacrifice in the world of modern-day medical practice – and malpractice. From its opening rural scenes, the film moves swiftly into flashback -- and into what was still recognizable Hindi movie terrain in 1980s: a holiday in Kashmir. It is there, on a promontory looking down at the Dal Lake, that a much younger Prashant and his friend Sudhir Rai (Amitabh Bachchan), both recent medical graduates from Bombay, first encounter a visiting literature professor (AK Hangal) and his daughter, Kavita. Prashant, the son of a magistrate, has his path cut out for him and follows it: he becomes a doctor, marries Kavita (Rakhee), and goes abroad for higher studies in gynaecology. Meanwhile his friend Sudhir, rescued from a life of juvenile crime by Prashant's father, also becomes a doctor, but chooses to stay in India and work in a regular hospital as a child specialist.

The two remain friends despite these varying choices. But the Prashant who returns from the USA is a very different man from the one who left. “Hamaare profession mein aage badhne ke liye raasta seedha nahi hai, tedha hai [The way to get ahead in our profession isn't straight, it's crooked],” he announces to Sudhir and Kavita. “I came back with such a big degree, did I get a job, have I been able to establish my own practice? No, because in our country it is much easier to go from ten lakhs to eleven lakhs than from ten rupees to eleven rupees.” Bemisal is not one of Hrishikesh Mukherjee's finest films, but what he captures here is the sense of entitlement that had already become the tenor of conversation among educated young Indians in the late 1970s and 80s, a growing frustration with bureaucratic hurdles, a feeling that the country owed them – rather than they it. “My father wanted to see me become a big doctor, and I will fulfil his dream -- by hook or by crook,” says Prashant without the slightest irony. He proceeds, again without irony, to sell his father's house to buy a new private nursing home, which starts to rake in money.

This raging financial success, it turns out, isn't sanguine. What Prashant passes off to his wife as his popularity (“teen maheene se advance bookings”) turns out to be a matter of accepting black money and cooking the books. Second, it is the start of the era of Caesarian deliveries and Prashant is shown deliberately encouraging them, even for what could have been regular births -- each operation and hospital stay bringing in additional moolah. (The film also makes a joke of the new fetish: Deven Verma's character, while getting engaged, buttonholes a gynaecologist to book an advance Caesarian delivery for his wife-to-be.) More complicated is the nursing home's role as a site of expensive, often illegal, abortions: here Mukherjee and his screenwriter Sachin Bhowmick falter. The film mixes up what it considers the morally unethical practice of secret abortions for “the unwed daughters of the rich” with the medically unethical – and dangerous -- business of conducting MTPs past the advisable date, for an under-the-table fee.

A case of the latter sort finally leads to the death on the operating table at Prashant's hands – though we never see the young woman. What we are given instead is the agitated figure of Aruna Irani, a receptionist at the nursing home who reports the death because she is still traumatised by a long-ago unplanned pregnancy and unwanted abortion carried out on the instructions of her callous playboy lover.

5 September 2020

The faults in our stars - I

My Mumbai Mirror column: the first of a two-part column.

What can Indian Matchmaking -- and

other recent takes on the arranging of marriages -- teach us about

ourselves?

|

| A still from A Suitable Girl, the 2017 documentary made by Smriti Mundhra, who has directed Indian Matchmaking |

It's been exactly a month since the reality show Indian Matchmaking (IM) took social media by storm. Indian-centric content, even when it's on international streaming platforms, rarely attracts non-desi audiences. IM broke through. Several non-Indian friends and acquaintances on my Facebook and Twitter timelines seemed as hooked to watching matchmaker Sima Taparia from Mumbai attempt to find suitable marital partners for her clients in India and the diaspora -- deploying not only her own social knowledge and networks, but also a battery of face readers, astrologers and life coaches. That realisation, that the rest of the world was watching 'us' with a mix of horror and fascination, was probably what resulted in Indian viewers displaying so much anxiety about the show's portrayal of realities that no Indian can be unaware of. The most obvious of these social facts is that marriage in India remains first and foremost a kinship alliance between families, and that therefore what must be 'matched' -- much before any individual preferences come into play -- is the caste and socio-economic background of the two people concerned. A second social fact: the patriarchal, patrilocal norms of North Indian upper caste society mean that the girl must be the one who leaves her family for her husband's home – by extension, leaving her existing life for a new one. As Taparia puts in early in the show, “In India, there is marriage and there is love marriage.”

Taparia, with her lines about fate and the alignment of the stars, has become an easy-to-mock target, the subject of many a Sima Aunty meme -- while at least two of the women she fails to find matches for, the Houston-based Aparna and the Delhi-based Ankita, have emerged as underdog heroines, being increasingly interviewed and feted for holding firm against Taparia and another matchmaker called Geeta, who labelled them “inflexible” and “negative”.

Watching the show, though, I felt like Taparia's clients were really a bit of a double act. The India-based families were all from traditional North Indian business communities, like Taparia herself, and seemed within her sociological comfort zone -- while the US-based diasporic candidates represented a much wider spectrum of professions and backgrounds – Guyanese, Sikh, Sindhi and Tamil Americans from Houston to Chicago, including lawyers, a motivational speaker and writer, a dance trainer, even a public school teacher.

Naturally, these two sets of clients had very different requirements and expectations. Someone like Akshay, the younger scion of a Mumbai-based business family who was only marrying because of his mother's insistence that 25 was way past marital age, may have mouthed a few platitudes about wanting a mental match with his partner, but anyone who watches the show can tell that any prospective wife for him would first have to meet his mother's requirements – in order to be able to effectively replicate her. Taparia's job in this scenario is finding a suitable daughter-in-law to fit into a large business-oriented joint family – which is a rather different requirement from finding someone who fits the psychological and professional expectations of an independent mid-career professional like Aparna.

As Taparia says early on, “In India you have to see the caste, the height, the age, and the horoscope.” How the system usually works is expressed in a rather revealing sentence from the father of one candidate: “Pradhyuman ki dedh sal ke andar dedh sau file aa chuki hai”. The subtitles call them “offers”, but the way Pradhyuman's father puts it -- “Pradhyuman has received 150 files in one and a half years” -- really tells you what Indian matchmaking usually feels like: a bureaucratic process, no less competitive and standardised than a job application. It's Taparia, in fact, who tries to bring a new personal touch into this database-driven arranged marriage scenario. But it isn't easy to get rid of the old.

Indian Matchmaking's director Smriti Mundhra (daughter of the late Jag Mundhra, who alternated between US-based exploitation films and women-centric Indian films like Kamla and Bawander) has known Sima Taparia for some years now, and has filmed her in more vulnerable circumstances. In her 2017 documentary debut A Suitable Girl, made over seven years, Mundhra tracked Taparia's real-life quest for a groom for her own daughter Ritu. An MBA whom we watch engage in a spontaneous appreciation of the merits of Macro versus Micro Economics with another female client of her mother's, Ritu is often silent on camera while her mother speaks avidly of her marriage. But she also speaks candidly to the filmmaker about knowing that she must marry soon. She does reject many candidates before agreeing to wed Aditya, who apart from meeting her parents' economic and caste criteria, has an MBA like herself and “is witty”.

The second young woman in A Suitable Girl is Dipti Admane, who works as a pre-primary school teacher. Touching 30, her inability to find a suitable match despite years of scouring the newspaper matrimonials has propelled her and her parents to the edge of depression. Commentators on Indian Matchmaking have singled out Nadia and Vinay's first-date discovery of a shared dislike of ketchup as a flimsy hook upon which to hang a potential relationship. The 'boy' who comes to see Dipti remains utterly silent while his mother makes sure Dipti can run a house and calls her job “good time-pass”. But all an excited Dipti marks after their departure is that he likes sweet lime juice -- like she does -- and that his birthday is the same as hers.

The second part of this column will appear next week.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 16 Aug 2020

11 June 2020

Faces in the crowd

As we are schooled ever more to view India's labouring poor as an undifferentiated mass, Kamal K.M.'s I.D. and Geethu Mohandas's Liar's Dice help us see our co-citizens in their individual humanity.

|

| A still from Kamal K.M.'s film I.D., in which an upper middle class migrant is forced to think about the life of a poorer one |

“A painter came to this house. I did not even ask his name. I mean, who does, right?”

The young female protagonist who says these words in the thought-provoking 2012 film I.D. is speaking to a male friend, who has to strain to understand what she’s on about – and not just because they’re in the midst of a raucous party. “I don't get you,” he responds at one point. Even to Charu (Geetanjali Thapa), her own words feel like the verbal equivalent of a shrug. There is a niggling sense that she could have done better – but following close behind is an attempt to reassure herself, that her lack of interest in the working class man who came to her upper middle class apartment wasn’t out of the ordinary.

The opening scenes of Kamal KM’s astutely crafted film have already established Charu as an ordinary member of her class and gender. She is a migrant, too, but that status does not mark her. Having moved to Mumbai recently from her home state of Sikkim, she shares a rather nice three bedroom apartment in Andheri with two other women her age. We hear her telling a friend on the phone that she has already booked a new car, though we know she’s still at the interview stage for a telecom marketing job. Meanwhile, through the glass walls of her bedroom, we see a city brimming with construction and labour. One man leads a buffalo through the streets, another kneels on the road to repair his auto, yet another carts eggs on a bicycle. Two urchins make a possibly obscene gesture as a young woman in a form-fitting dress climbs into her car.

When a man arrives to repaint a wall in the house, Charu lets him in, a little grudgingly, asking only one question: how much time will the work take? She is not exactly rude, but she displays the wariness that the upper middle class, likely upper caste Indian woman has internalised about the poor or lower middle class man. When the painter squats beside her to help her pick up some broken glass, she is standoffish. She does not offer him water until he asks. When she hears a thud, her first instinct is to tiptoe out of her bedroom looking for signs of violence, as if she fears a dacoity or worse. So distant does she feel from this stranger's humanity that she can't bring herself to touch him to revive him. She doesn't even think to sprinkle water on his face. Instead her only instinct is to call for help – the aunty downstairs that she has never before spoken to, the old security guard whom she has never before accompanied to the roof where he has to go each time the building lift misbehaves.

|

| Gitanjali Thapa sets out to trace an unknown man's identity in I.D. |

|

| A still from Liar's Dice, India's official entry to the Oscars in 2013. |

But it works as a companion piece to I.D., both films bringing into focus the India we consider normal – in which a man can simply disappear, with no-one held responsible for what happened to him. As even our existing labour laws are suspended in state after state, with governments using the pandemic as a cover for less regulation and oversight of working conditions, the lives of our nameless, faceless co-citizens are being pushed ever more out of sight. I.D. and Liar’s Dice give us a rare chance to start seeing.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 17 May 2020

10 June 2020

Isolated incidents

Placebo takes a personal deep dive into one of India's premier medical colleges and comes up with a disturbing, affecting vision of where we’re headed.

In 2011, a young filmmaker made a visit to his younger brother Sahil, who was studying to be a doctor at India’s premier medical college, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi. It was the time of the annual college festival, Pulse, and as happens during ‘fest’ season, enthusiasms and emotions were running high. Before the night was over, Sahil had been admitted to hospital, with his right arm so badly damaged that he would not be able to return to the hostel for three months. The twist, though, is what made the tale possible: Abhay, the filmmaker brother, didn’t go home with Sahil. He decided to stay on his brother’s hostel instead, gradually inserting himself in – and his handycam is – into life on the AIIMS campus. And so began the dark, dark cinematic ride that is Placebo.

Free to stream on YouTube, Placebo is a strange and vivid film, combining special effects, hand-drawn black and white animation, found footage and still photographs with Abhay Kumar's footage. The 96 minutes that we finally see on screen apparently draws on 800 hours of footage, and the filmmaker edited 80 different versions before finalising this one. That process sounds terrifying. The film is a little less so – but not by much.

Placebo is a film about many aspects of the Indian present seen through a sharply angled lens: education, privilege, individualism, community, institutional failure and our failures as a society. Kumar starts by pointing to the competition that these students have dealt with to reach these peeling hostel buildings. According to a statistic cited in the film, MIT has an admittance rate of 9 per cent, and Harvard (the university, I'm assuming, not the medical school) has one of 7 per cent. The rate for AIIMS’s is 0.1 per cent.

Kumar’s voiceover repeatedly emphasises the 'brightness' of these students, and they mirror his framing, telling stories that reveal their sense of achievement in having, as we say in North Indian slang, “cracked” the medical entrance. But watching these nerdy young men talk about girls or play music or collapse in laughter after a doobie or a round of bhang pakoras consumed appropriately on Mahashivratri, what one is struck by is precisely how ordinary their desires are. They seem like any other 23-year-olds, with the same fears and desires and anxieties as young men everywhere – just bearing a heavier weight of academic/professional expectation, without the emotional or therapeutic support structure needed to deal with the pressure. Those who break, the film shows, are not helped to mend themselves. The cracks are papered over, and the fragments swept under a carpet.

All that the Indian educational system seems to have given these young men is the heady sensation of entering an elite. The path from AIIMS could take them on to a well-paying career as a doctor, or a powerful position in the Indian civil services, or to more specialised medical research in India, but more desirably in the USA. There is ambition aplenty – but even among the four or five students that Placebo keeps in fairly tight focus, there is no sense of a vocation.

There's Sethi, a fair North Indian chikna hero type who says his greatest desire is to “look good naked” – “like the guy in American Beauty”. He categorises the species called girls into different colours: “There are orange girls, there are green girls”, and the one who got away, “she was so white”. Sethi wants to be confident enough to ask out girls in America. Getting to America is his second ambition after getting to AIIMS.

There's the tall, bespectacled, pudgy-faced Saumya Chopra, who begins his AIIMS life terrified of ragging but becomes the senior who's suspended for two months in 2008 after a Supreme Court judgement makes the authorities crack down on ragging incidents. There's a tangent here that the film doesn't follow, about how our educational culture is so toxic and so isolating that ragging was the only way to forge intergenerational connections.

There's K, the most meditative of the lot, whose self-reflection does not in fact help him deal with his inner demons. “The respect I have for the word doctor is far more than the respect I have for me as a doctor,” K tells Abhay.

Ostensibly at the other end of that spectrum is someone like Saumya, who's only answer to why he wants to be a doctor is “My parents want me to be a doctor.” “What do you want?” asks the filmmaker. “Whatever my parents want,” comes Saumya's reply. “Our life is a debt to our parents... You can't pay it back ever but one must try at least.”

Saumya's words reminded me of another young Indian captured on camera in a documentary: a Durga Vahini leader-in-the-making called Prachi Trivedi, in Nisha Pahuja's superb 2014 film The World Before Her, who says she would do whatever her father wanted, because she was eternally grateful to him for not having aborted her as a female foetus.

This idea that our earthly existence is essentially beholden to our parents feels chilling to me, and will do to many who see human beings as free-standing individuals. Yet the flip side of that individuation is also a chilling aspect of Placebo, and particularly resonant in these solitary, socially distanced times. As K says to the filmmaker: “Even though we have been talking for so many months, you and me, we're isolated, that is a fact.”

It is a bleak vision of humanity, but perhaps also a self-fulfilling one.

https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/opinion/columnists/trisha-gupta/isolated-incidents/articleshow/75513645.cms??utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/opinion/columnists/trisha-gupta/isolated-incidents/articleshow/75513645.cms??utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

16 February 2020

Love, Lies and Videotape

How Francois Truffaut, who'd have been 88 this February, created an on-screen alter ego from 1959 to 1979, weaving happily between life and fiction

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in Love on the Run (1979), the last of Francois Truffaut's Doinel films. |

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 9 February 2020.

Under the influence

The under-watched classic Bigger Than Life turns family drama into almost-horror, with prescient warnings against modern medicine and delusional masculinity

The first 20 minutes of Bigger Than Life seem to paint a picture of the perfect family man, who’s also a hard-working, pleasant colleague. A schoolteacher in suburban 1950s America, Ed Avery (James Mason in a career-defining performance) is the nice guy you ask to help push your stalled car, the guy who lets the kid in detention go if he can name one Great Lake out of the five, the guy who sprints on to the last bus after school to work a second job at a garage.

But those first 20 minutes also show us that Ed is also the sort of guy who thinks he can handle everything, and do so alone: he hasn’t told his wife about the garage job because she’ll think it’s beneath him, nor mentioned the pains he’s had for six months because he thinks they’re nothing. So it doesn’t seem surprising that when he’s forced to go to hospital after a blackout, his first instinct is to instruct his little son Richie to be “the man around here” and “take care of your mother”.

On the surface, Nicholas Ray’s film is about the dangerous mental side effects of a miracle drug for the body. Ed is diagnosed with a rare inflammation of the arteries, and treated successfully with cortisone – until he starts to take it in excess. The mood swings, paranoia and manic depression that result only reinforce his impaired judgement, making him take still more pills. Screenwriters Cyril Hume and Richard Maibaum based the script on an article called ‘Ten Feet Tall’ by Berton Roueché, medical staff writer for The New Yorker, about a real schoolteacher’s experience with high-dosage cortisone. And though this is 1950s America, and patient and doctor are well-acquainted, even friendly, the film clearly indicates how alienating hospitalisation is: the non-stop tests, the solitary confinement, the ghostliness of barium meal, the unrecognisable medical jargon in which you hear your own body described.

But Ray, a director more famous for films such as Rebel Without a Cause and In a Lonely Place, was a man both ahead of his time and able to see into the depths of it. Released in 1956, when much of America was watching the era-defining sitcom Father Knows Best, Bigger Than Life revealed the frightening cracks in that idyllic ’50s family picture. At one level, Ed Avery’s symptoms are those of a mentally ill man, but he can certainly also be viewed as a barely-exaggerated version of the ordinary neighbourhood patriarch, the father who thinks he knows best even when he clearly doesn’t. This is the man insecure about being a “male schoolmarm”, who also has delusions of grandeur about schooling the nation. He insults his wife (“What a shame I couldn’t have married... my intellectual equal!”) and pushes his child beyond breaking point in the name of prepping him for the real world (“If you let it at ‘good enough’ right now, that’s the way you’ll be later on.”).

The film is also a powerful indictment of the pressures of life in a consumerist era, for a man trying to give himself and his family a good life on a single schoolteacher’s salary. The Averys’ house is filled with posters of faraway European holiday destinations, and there are wry, hopeful conversations about vacations and “getting away from it all” – while the camera often focuses on James Mason’s watch, and time and lateness is a frequent topic. The tight budgeting that makes Ed work a secret second job has as its flip side the grandiose display he indulges in when under the influence of the cortisone: hustling his wife into a fancy designer store, being rude to the saleswomen, and insisting on buying her two expensive dresses with a cheque that eventually bounces.

The more unbalanced Ed gets, the more he is convinced that he is the only smart person around. The milkman’s jangling of a bell seems to him deliberately designed to annoy him “because I work with my mind”, the other drivers on the street irritate him, his son and wife disappoint him, and the children he teaches for a living seem to him idiots. “We’re breeding a race of moral midgets,” he declares at a PTA meeting, eliciting mostly gasps of disbelief – but also a couple of votes for future school principal.

Watching Bigger Than Life in 2020, the self-aggrandising family man who thinks the country needs to do away with “all this hogwash about self-expression, permissiveness and emotional security” and focus on inculcating “a sense of duty” feels terrifyingly familiar. He might be your neighbour, your uncle, your father or your boss. And his condition is getting worse, under the influence of a collective drug called nationalism, being doled out for free at a counter near you.

Published in Mumbai Mirror, 2 February 2020.

30 December 2019

"Fiction should prophesy the future": Benyamin

(A short author profile of the Malayalam writer that I did for India Today.)

Benyamin—the Malayali writer Benny Daniel—did not grow up a reader. Other than the Bible, which was read every night before supper in his orthodox Syrian Christian household, he had read no other books in his childhood. He began to read after moving to Bahrain in 1992. For the next seven years, he read voraciously, while working as a project coordinator at a construction site. Writing grew organically out of a readerly desire. “I wished to read about the situations I felt and saw around me. But I realised nobody was writing about it yet. So, I started,” he says in an email interview.

His first short story appeared in the Gulf edition of Malayala Manorama in November 1999. There has been no looking back. Now the author of over 16 books in Malayalam, Benyamin remains prolific and hugely popular in Kerala, to which he returned in 2013. His Aadujeevitham ran into more than 100 editions, selling over a hundred thousand copies, and a Malayalam film version, starring Prithviraj, is planned for release by end-2020. The book

also did well in Joseph Koyipalli’s English translation as Goat Days (2012). Three other Benyamin novels have appeared in English translation: Yellow Lights of Death (2015), translated by Sajeev Kumarapuram; the JCB Prize winnerJasmine Days (2018) and, most recently, Al Arabian Novel Factory (2019), both translated by Shahnaz Habib.

Together with its ‘twin novel’ Jasmine Days, Al Arabian offers a rare portrait of urban life in the Gulf through the eyes of diasporic South Asian characters. Jasmine Days was told in the winsome voice of a Pakistani radio jockey called Sameera, the narrative echoing the young woman’s move from sheltered ignorance to humanitarian and political awakening. Al Arabian uses an even more open-ended device; the narrator Pratap is a Toronto- based Malayali journalist hired by an “internationally acclaimed writer” to help research a novel about present-day life in West Asia.

Among the joys of these books are the conversations across social, religious and national lines: between Shias and Sunnis, Arabs and South Asians, Malayalis and Hindi/ Urdu speakers, Third World passport-holders and those with First World privileges. “When we are inside India, we see a Pakistani as an enemy. Bangladeshis and Nepalis see us as enemies. But in a third country, we realise we lead the same kind of life. We eat together, work together. It dilutes the fear among us,” Benyamin says. These real-world diasporic encounters are supplemented by virtual ones. “Cyberspace deletes the borders drawn by politics,” in Benyamin’s words. But in his fiction, Facebook, Orkut, Viber, WhatsApp and email also enable unlikely connections and reconnections, secret affairs and the creation and destruction of new identities. This is of a piece with Benyamin’s penchant for “demolishing the wall between real and fiction”. He often makes his narrator a writer, a figure who listens to stories, or presents eyewitness accounts. In Yellow Lights, the writer is even called Benyamin.

Based on what is available in English, Benyamin comes across as deeply curious about the stories he hears. But these four books also reveal a keenness to place those personal stories in social and political context. And in this, he is fearless. Goat Days, in which a poor Malayali migrant is turned into captive labour in the Saudi Arabian desert, is banned in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Characters in Jasmine Days and Al Arabian argue often about politics, challenging and being challenged by each other’s posi- tions on colonialism, oil-rich capitalism, dictatorship and religious conflict. “In the age of visual and social media, fiction-writing does not have entertainment value. It is a purely political activity,” Benyamin says. “It should shine a torch upon our dark areas. It should prophesy the future.”

Al Arabian Novel Factory takes that responsibility

seriously. Pratap’s taxi ride

from the airport into ‘The

City’ transports him—and

us—into the heart of a

dictatorship. The man just

ahead of Pratap is forced to

get out of his car by a soldier

demanding to see his phone.

In an instant, he is on the

ground, being thrashed with

the soldier’s gun. His phone

is smashed, and he is forced

to sing the national anthem.

A petrified Pratap awaits his

turn. But it turns out the taxi

driver was right: “This is a

very safe city for tourists.”

Al Arabian Novel Factory takes that responsibility

seriously. Pratap’s taxi ride

from the airport into ‘The

City’ transports him—and

us—into the heart of a

dictatorship. The man just

ahead of Pratap is forced to

get out of his car by a soldier

demanding to see his phone.

In an instant, he is on the

ground, being thrashed with

the soldier’s gun. His phone

is smashed, and he is forced

to sing the national anthem.

A petrified Pratap awaits his

turn. But it turns out the taxi

driver was right: “This is a

very safe city for tourists.”

Unlike Goat Days, Jasmine Days and Al Arabian Novel Factory feature mostly middle-class members of the South Asian diaspora: people who have built relatively prosperous lives in West Asia as nurses, doctors, restaurateurs, journalists or businessmen. And both books repeatedly show us these people being apathetic or worse, actively opposed to all local political resistance against the authoritarian regime. Silence is apparently a small price to pay for the privileges they enjoy. What doesn’t affect them directly, they turn a blind eye to. It is hard not to see that self-serving quality all around us in present-day India. Benyamin doesn’t mince words on the subject. “We have almost abandoned democracy and are rapidly moving to autocracy. In the name of strong leadership, a majority of Indians have become fans of fascism. But we really don’t know the rights we are going to lose in this dangerous game.”

Published in India Today, Dec 27, 2019.

Note: You can read my review of Jasmine Days here.